|

1. Preparatory violin study

Lucia, my violin teacher, who I had not seen in months, approached me online in the spring of 2020 when we were all hunkering down for what would be a couple of years, though none of us knew that then. She suggested I start up my violin lessons again on zoom. Lacking distractions from work (in my home office), I thought, “why not?” But this time I would take a more systematic approach. I would take David’s advice and follow the RCM program to put structure into my learning. Lucia thought this was a stellar idea, and so I bought the RCM Preparatory Violin books: technical study and repertoire, keen to crank up again on a clearly defined path. Looking through the books, though, I became fearful: this was preparatory? It was hard! Worse still, the preparatory technique book spanned from preparatory to grade four; sneaking a peak ahead was the stuff of nightmares: notes all over the place, doodads over the notes, fancy scales under long phrase lines and all nature of scary stuff. I should come clean and admit that I studied piano as a child (early Pleistocene era), so I was not musically illiterate. The six years I spent learning to play the piano with French Canadian nuns (tough task masters) included theory and, helpfully, solfège, which I was to meet again, unexpectedly, in fiddle class a little further down the track. But the system at Notre Dame D’Acadie was organized differently from RCM programs so I could not say what grade I reached. Nonetheless, not having to learn theory and sight reading from a standing start was helpful: the cognitive load in reading music and playing it at the same time is significant and should not be underestimated. All the same, I had to see the notes on the page as points on a violin string. This was new. I could picture, say middle C (along with the scales, arpeggios, etc.) on a piano but I had to find it on the violin and hear it and feel it in my hand, so I wasn’t (desperately and unrecognizably) off pitch. Preparatory began sensibly with the A major scale, the most basic scale on a violin, played on the easiest string to reach. This was friendly. I knew what a major scale should sound like, so I could practice towards it sounding right. I could reach these notes, though they were kind of pesky to find. With the A major scale, I had the A major arpeggio over one octave. I had single bows only: one note, one bow. I could do this!!! I graduated to the D major scale. So exciting! By now I could reach the D string but going from the A string to the D string was harder than the other way around. And then, the D arpeggio. I was rocking. The études were another matter. On the first page was one in sixteenth notes going up the D scale but it had accented quarter notes in it and dynamic shifts, and… harmonics? What the hell? Where did these come from? My violin teacher admitted that she favoured the Suzuki approach to the RCM program, as RCM tended to erratic étude and repertoire choices and levels of difficulty varied even within a single level. But Suzuki was for children, I thought. Well, she explained, adults do it, too. It is oriented to ear-training. The downside is that Suzuki learners are not as strong at sight reading as RCM learners. At the time, I was senior faculty at a large urban university, seconded to a senior administrative post. I had to solve faculty problems and answer to university leaders throughout my day—all on Zoom—which limited my available practice time, and on some days, wiped me out past even starting the depressing regimen of hunt and peck scales. But motivated by a fear of making a total ass of myself in front of an examiner accustomed to 5 year olds capable of mastering this content, I pushed onwards. I stretched, I practiced, I recorded myself and self-critiqued. I watched superstar violinists on YouTube, and listened attentively, studying how they held their violins and their bows. I practiced with my husband playing the piano or the ukulele; I played to recorded tracks; I sent video-recordings to friends and family. Mostly they were encouraging, and not without incredulity that I would undertake such a project at my age. My daily practice was organized around a linear read of the technique and étude book, followed by my big moment: my repertoire pieces. Two! I felt practically ready for Carnegie Hall in comparison to where I was with Twinkle, twinkle little star a year ago. And as such, my practice was shaped as a daily scrum with my violin, progressing through each section of the preparatory course that I would have to perform for my examination, though the sightreading selections came later, as did the ear training. Ear tests I got from David, whose musical knowledge was immense, and patience, even more so. Most of the repertoire selections were sensibly scored in the keys of A and D but some joker had put in two pieces in the key of C major, which is NOT a friendly key on the violin. At least, not at this level. The pieces had names like Playing ball and Pony trot, which felt a little undignified for a mature woman. Nonetheless, I tried as many as I could manage and settled on a pretty lullaby called, evocatively, Song, and another rather quirky piece that was quite dramatic in character, called, The old jalopy, which had a cute slide at the end of it. I practiced these pieces till my fingers were raw, so keen was I not to make a total fool of myself on my debut examination. David and I practiced together once a week, he on the piano part provided in the repertoire book. From this, I got the bright idea to tape his part, so I could play along to it during my daily practice. The exemplars provided by RCM were all too fast, plus they were played by professional musicians with beautiful tone, vibrato, perfect intonation. Impossible models…

0 Comments

Just fiddling around

1. Fiddle dee dee Heather Lotherington I took up the violin in my 60s. It was early summer, 2018, shortly after my daughter had taken me to task on a constant refrain that my next car would be a Porsche. On my birthday, she met me at a Porsche dealership and insisted the two of us test drive the car of my dreams. Midway out of the lot, the exquisite sports car’s battery went flat, and we drifted into traffic. It was horrifying—but a dramatic lesson. Life waits for no one. (I bought an Audi TT instead). When my husband suggested a lovely gift idea for my birthday, I declined and asked for violin lessons. Soon after, I had a rental violin in hand, and a month’s lessons lined up with a local teacher, who I found online. And thus began my violin journey. I remember my first lesson: I had no idea how to hold the violin or the bow or that I needed a shoulder stand to help position the violin more comfortably on my shoulder. I didn’t even know how to pick up my instrument. It was a very cold start. I reckoned that playing the violin—an idea in the back of my mind for some time—might help stem my arthritis and encourage some flexibility in my increasingly knobby, stiff fingers. This wasn’t the primary motivation for learning, but it did help to spur me along. I had put off my dream of playing the fiddle for long enough. If I didn’t get going, my hands were going to become inflexible claws. Plus, how hard could it be? The fiddle is commonly played by countryfolk by ear, and you see even little children wailing away on violins. Fast forward past the commitment of buying a violin and a sustained period of caterwauling that caught the attention of local tomcats, past the perpetual state of terror at lessons, a badly inflamed shoulder, unending frustration, and constant tweaking of violin, shoulder rest, chin rest, bow to find a position where my instrument felt even quasi-comfortable. It would be lovely to sugarcoat just how miserably trying this beginning period was. It was by sheer dogged determination that I survived. My bowing was crooked (it looked straight to me, but such is parallax), sliding towards the fingerboard, which created an awful tone. My bow (right) elbow was all over the map instead of steadily in position for the string being played, so I “string-crossed,” or hit more than one string at one time. This can be done by design; mine wasn’t. (Think donkey braying noises.) My bow bounced off the string when I lowered it to play. I could only reach the top two strings (E, A) with my left (violin) hand and I had absolutely no idea how violinists got all twisted around to reach much less play the D string and the bottom (G) string. My left shoulder and back ached to the point where I had to stop entirely for a few months and get physiotherapy to repair the tense, weak, underused muscles I needed to build. So, the first hurdles were painfully physical. My teacher, Lucia, was understanding. “No one is born playing the violin,” she would say. There was a learning curve just to holding the instrument. But there was also a focus hurdle. I wanted to learn to play the instrument, and my teacher did her best to guide me. On her advice, I bought a learner book. But my agenda was vague and unhurried. I would practice the same songs again and again, and sound just as bad as the last time I played them. I was mystified how violinists found the exact notes on an unfretted instrument when there seemed to be so much room for error. Practice was demotivating to say the least. After several months, I could feel my teacher’s impatience as she tried to move me ahead in my learner book to attempt a simple jig. I crumbled. I couldn’t tell where those high notes were and jumping up two strings from the D, which I could finally reach, was taxing. I would practice and hate every moment. And then Covid-19 hit and life came to a grinding halt. I stopped playing. Looking back, I now see two glaring problems I faced during that first unproductive period:

I was horribly disillusioned. Monitoring my increasing disheartenment at plowing through my beginner book, my husband made a sensible, informed suggestion: sign up for an examinable music program. So I did. Learning to play a musical instrument, even at an elementary level, is going to take effort and persistence. Any activity that helps you to maintain your enthusiasm should be welcomed. Here are five ways I assist myself. You might think up your own list.

Both programs and institutions were similar in size, scope, and intent. They had similar goals of producing professional musicians and skilled teachers.

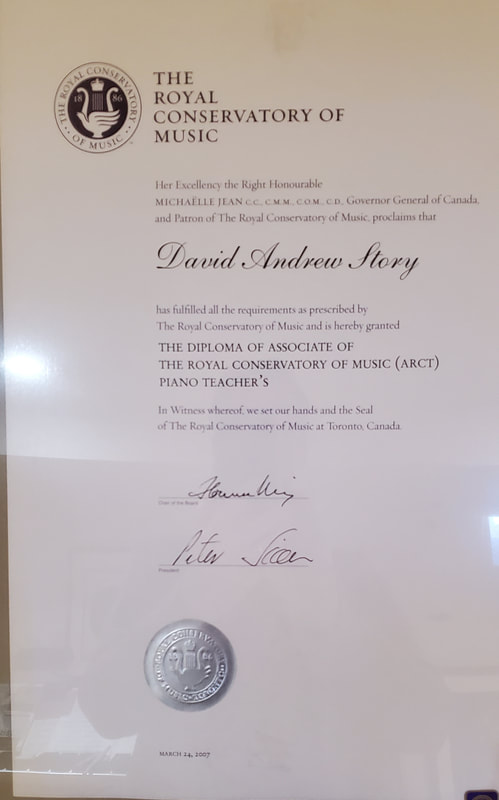

At Berklee I studied jazz composition, a creative and primarily cerebral affair. The music courses were interesting but not too challenging. In contrast, the Royal Conservatory of Music (RCM) was a full on physical experience that challenged my endurance, courage, and self-image. At Berklee I excelled easily because I came to the experience with considerable professional experience behind me. Classical piano on the other hand was a new disciplined practice that I had no experience or preparation for. A Berklee I was trained to be an employable musician and its skills still work. At Berklee, creative wondering was encouraged. This lead to all sorts of self indulgent activities. However, at the RCM I was challenged not to be "creative" but to be skilled and competent. At the RCM I decided for the first time in my educational life to simply follow directions, do what I was told, and see what happens. The result of all this obedience? I really learned how to play the piano beautifully and realise my potential both as a player and teacher. Being "creative" is easy if you use yourself as a reference for judging the output. But, playing beautifully according to independent assessment of a jury is not easy. So, Berklee was easy, the RCM not at all. If you would like help preparing for either experience, call me. David Zoom whiteboard notes from a piano student's lesson A student asked me questions on practicing. Do I practice every day, how long do I practice, when do I practice, what do I practice? How do I keep my enthusiasm for drumming year after year? Here are my answers.

As many people know, I took up the drums at age 50 after an adult student challenged me by saying I had no idea how difficult it was to learn as an older adult. I took the challenge. So, this blog is about my percussion practicing. (When my musical colleagues ask why I started drumming I tell a more colourful story that involves my misperception that drumming would be a cheaper mid-life crisis solution than buying a red sports car.)

If I can help and encourage you on your musical journey, call me. David aka "sticks Story" PS. I now cart my drums around in a red Cadillac. Not quite a sports car, but more drummer friendly. How much practice, time, and effort did earning my Royal Conservatory Level 10 and ARCT Pedagogy diploma take?

|

You've got to learn your instrument. Then, you practice, practice, practice. And then, when you finally get up there on the bandstand, forget all that and just wail. AuthorI'm a professional pianist and music educator in West Toronto Ontario. I'm also a devoted percussionist and drum teacher. Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed