|

0 Comments

1. Deliberate practice

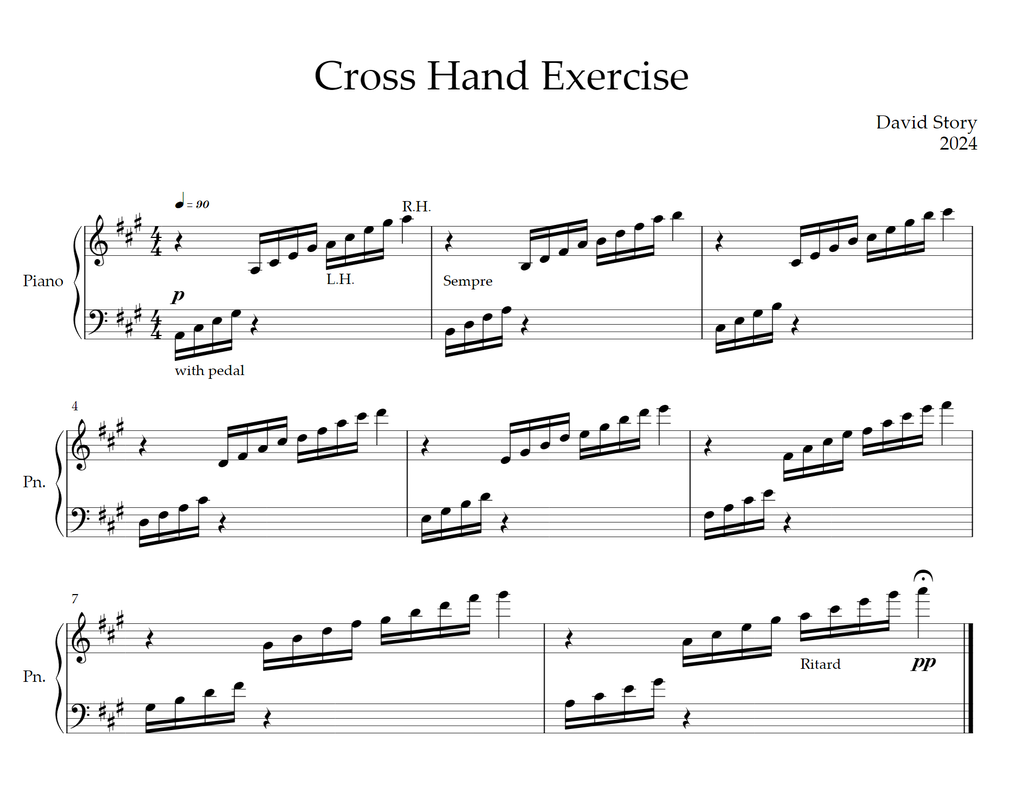

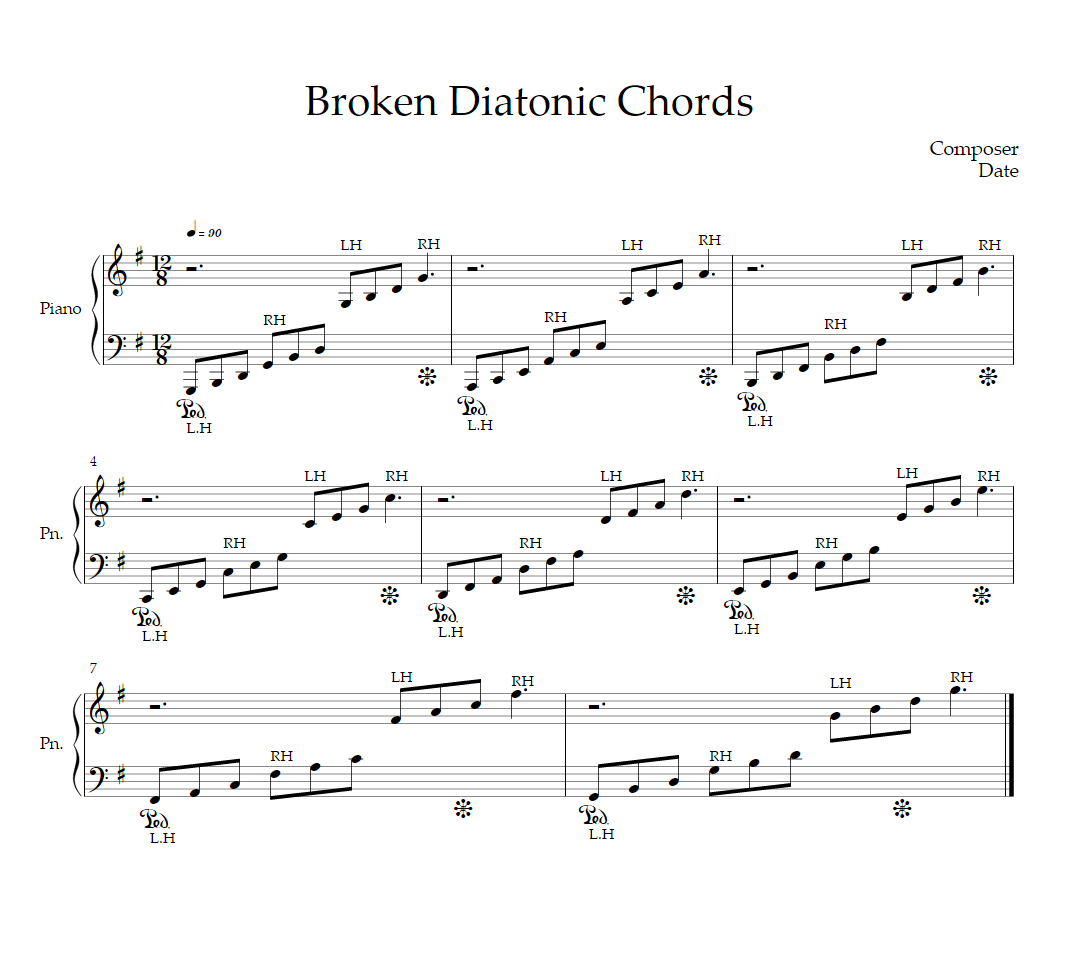

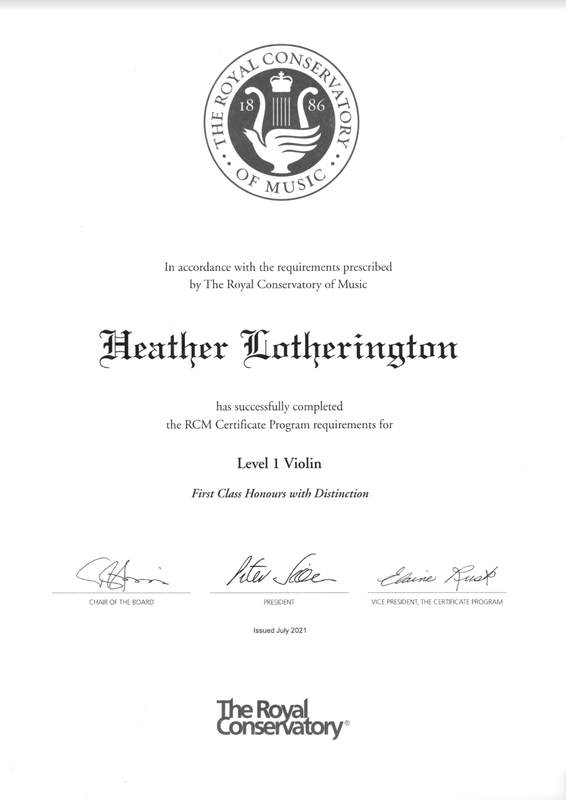

I have always listened to classical music, which I have loved since I was a child. My father listened to opera; he loved Beethoven. He knew nothing more than he liked this music and I never thought to ask him how he had met it in Sydney, Nova Scotia, growing up in the great depression on the wrong side of town. Growing up in the Maritimes I was also exposed to fiddle music as a fundamental feature of Maritime culture. And, of course, my coming of age coincided with the great folk festivals of the late 60s and the dynamic rock revolution of the 70s and 80s. Suffice to say, I have familiarity with a broad spectrum of musical genres. I progressed doggedly, passing my grade 1 examination, 7 months later (95). Playing before an examiner was, as Rory had voiced a couple of years ago, an intimidating experience. There is you and your violin and the marker and nowhere to hide. As a professor, I was used to making presentations before audiences of diverse sizes from a few people to hundreds. But I spoke about material that I had researched, taught, and written about as an expert in my field. I supported my talks with fancy, attention grabbing multimedia. I got to stand behind a lectern. I was never as exposed as I was playing the violin for an audience. Just playing for my teacher could make me break out in a cold sweat. But music is meant to be played with and for others, so performance is an essential skill. I had to practice performance as well the many physical skills intrinsic to playing a musical instrument. When I visited family in the Maritimes, I played for my mother in hospital (woe betide anyone else trapped in the same room). My brother would groan. My sister would praise my efforts, and acidly remark that no other 60 year old in the family seemed to be learning anything quite so difficult. My 90 year old mother would ignore her sniping children and merrily sing along. So would my daughter, in support of her grandmother slowly fading with dementia. I accumulated tunes I picked out by ear that mom could still sing: Frère Jacques, Row, row, row your boat, Old MacDonald had a farm and suchlike. I sent a tune a week to my sister (mom’s caretaker) to play to her. This became my weekly learning-by-ear project. On trips to visit David’s parents, both musicians, we gave concerts. Playing with David made me sound so much better. My father-in-law, a cello player and a choir singer with a practiced ear made the suggestion that I sing along to my playing for a check on pitch fidelity. Though I am not sure my singing is any kind of asset, singing in your head really helps to hone pitch, a necessity in playing any unfretted stringed instrument. It was a good call. The term “deliberate practice” I was familiar with, but it wasn’t until my list of scales and études grew too onerous to plow through daily that I had to schedule what I could and should do on a given day. This reshaped my practice, which by that point had grown from a half hour to 45 minutes stretching into an hour daily. I had to choose scales matching the requirements of the études and repertoire pieces, and make sure that I managed to do everything over the course of a couple of days. By the time I reached level 4, I had a grid outlining four days of technical studies: scales, arpeggios, double stops, which themselves followed left hand and bow warm-ups and preceded études and a selected repertoire pieces. Within each section, I had specific practice points. The job was to try to focus on one thing at a time—dynamics, pitch, expression, slow bowing, clean string crossing, and more, though I had to be responsible for everything in the end. Violin learning is intensely physical as well as cognitively demanding and aesthetically challenging. Practice is complex. I have remained with the same teacher, an excellent critic, demanding of attention to details and a seemingly endless font of advice on how to do sometimes minute things that contribute to violin playing. She is a concert violinist, who teaches. Now retired, I can be flexible with her timing, but I am constant. Even on weeks when I feel I have acquired absolutely nothing in practice, we have our lesson. Sometimes it is highly informative. Sometimes I feel like a four year old who can’t tie my own shoelaces. Always it is a learning experience. Nine months following my Level 1 exam, I passed Level 2, (88), and a year after that, Level 3 (87). Lucia was frank: the period of preparation gets longer with each level and the marks slide with the increasing level of complexity. I am hoping to be ready for my Level 4 exam in a month or two and have extended my preparation accordingly. Lucia says, there is no hurry. I now practice once or twice a day for an hour to an hour and a half. I stretch and roll out tight muscles to keep as much fluidity as possible playing an instrument infamous for causing neck and back pain. Five years after that first birthday gift of a rental violin, I treated myself to a handmade carbon fibre violin that I fell in love with. I have upgraded my wooden violin and acquired two quality bows: a carbon fibre for fiddle music, and a pernambuco wooden bow for best tone in classical music. The idea that I might stop playing is now ludicrous—this is an immense journey and I have got this far. There is no turning back! My teacher says, you can become a doctor in 7 or 8 years, but it takes a lifetime to become a musician. I still resist beginning my practice some days when listening to myself is depressing, though less so than in the early days, when dogged repetition was required to get anywhere at all. I now also take fiddle classes in addition and sometimes play fiddle tunes with friends who are more advanced but gracious and tolerant. Come to think of it, my pitch is better than some of the other fiddlers who haven’t paid such close attention to detail as I have had to with private lessons. I am working on vibrato which I find fearfully difficult. Lucia reassures me. This is a long process. Just keep working every day and slowly, there will be progress. Heather Lotherington 1. Committing to the instrument!

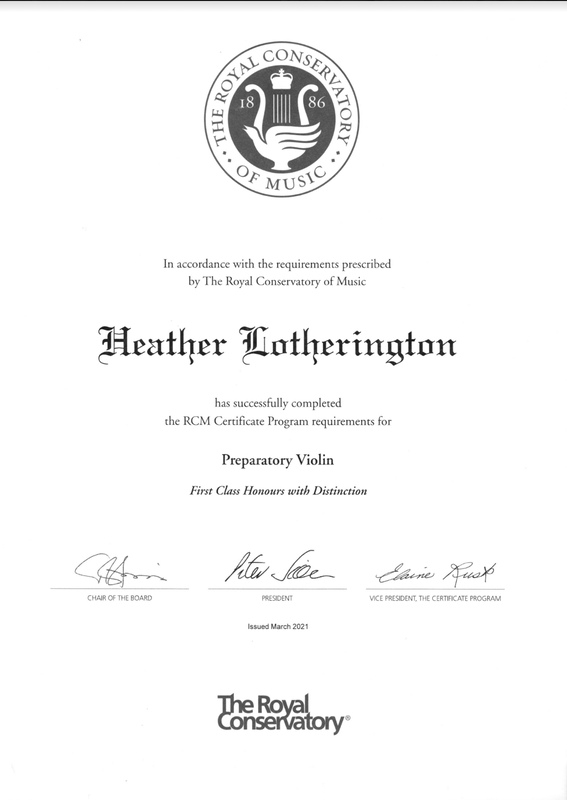

I made the first of my solid commitments to learning to play the violin in the early months of my learning journey (before the beginning of the pandemic) when I returned my inexpensive rental instrument to Long & McQuade, and went to The Sound Post to buy my very own violin. Terrified to showcase my elementary playing skills, I asked the salesclerk to play the array of violins he had picked out that were within my price range. This he gladly did—perhaps not for the first time, I thought. After all, a sale is a sale. Buying a stringed instrument and/or a bow carries a trial period. My teacher, Lucia, had made it very clear that I would need to play a new instrument for a while to know if it felt right. My criteria for feeling right were rather slim at this stage, so I chose the most resonant violin complete with case and bow, and just looked at it for a while when I got it home. It was a lovely student violin and it got me through the first few years of learning. My problems at this stage of learning—level 1—were myriad: I had insufficient strength in my fingers (to hold down the strings) and back (to hold up the bow without tension) and lacked the requisite flexibility in my shoulders, arms, hands and wrists to reach all the notes on a violin. My joints slowly opened up as I strove to reach hard to hit notes and press hard enough on the string to make a good sound—or maybe any sound. But this did not happen overnight, and trying too hard just caused more stress injuries. Listening to myself was still unutterably dismal and horribly demotivating but I just kept pushing through on blind faith. When I received the final mark on my embossed RCM assessment for the preparatory level, I wondered for a moment, if they might have sent the result to the wrong person. 91? First class honours with distinction? I was amazed! With this positive reinforcement, I launched headfirst into Level 1. On the technical side, I graduated to A minor harmonic (check!) and A minor melodic, which was a scale I had never heard of before. The dreaded C major scale made an appearance. I also had G major—on two octaves. There would no longer be any excuse for avoiding the G string. Not only did I have to learn the G scale starting on the open string, the lowest note on a violin, but the C scale began on the G string with the third finger. No tonal reference point. Tricky! There were also double stops: playing two strings at the same time. These were open strings: perfect fifths. They sounded beautiful but it was devilishly difficult to balance on both and keep the hee-haw sounds down. Turning the page to the études, I saw a definite escalation. My studies included pieces with accidentals, double stops, harmonics, slurs over four notes (oh come on!) and sixteenth notes, though fortunately not altogether in the same place. They presented a kind of choose your poison smörgåsbord. I sat, listened and read along to every piece in the repertoire book, all played by professional violinists who sounded hopelessly perfect and beautiful. I tried to judge the most doable pieces for myself. These were not necessarily the easiest, but I did not want pieces deliberately pushing the boundaries of the next level. Showboating is for young people with good joints and easy flexibility, who also play on proportionately smaller violins. No such luck for seniors. I listened for something else, too: I wanted to play what I liked. There was a wide variety of pieces offered, so this was not hard. I met composers, such as Dmitri Kabalevsky, whose compositions I loved, and found traditional songs, such as, Un Canadien errant, a beautiful, haunting piece that I have known since childhood. I found a lovely ballad written as a duet, and asked Lucia to record the second violin. When she sent it and I played along, magic happened. Playing against a beautifully performed second violin made my first violin part sound so much richer. I played and played that piece. I still play it years later to practice more advanced techniques, such as vibrato. Cycling back to earlier pieces to practice new skills, coincidentally a feature of the Suzuki method, was reassuring and affirming of my progress. Thus far, I had organized my daily practice in terms of a linear run through the technical exercises, studies (now two of them) and selected repertoire pieces. Though still generally useful as an organizing principle, linear study was becoming physically unrealistic. I needed to learn to do deliberate practice. 1. My (heart-attack inducing) preparatory violin examination

When my teacher, Lucia, thought I was ready for the examination, about 6 months in, I nervously opened the appropriate account on RCM and applied for an examination date and time, choosing a time when my playing would not disrupt any of David’s regularly scheduled musical activities and he could accompany me on the two repertoire pieces. I chose 9:30 am, giving me enough time to wake up, eat, warm up, and—recommended by Lucia—retune my violin to the conditions of the basement where the zoom exam would be held. A month before the examination my nerves started getting the better of me, so I intensified my practice time on the weekends, bearing down on my scales and arpeggios, determined to get my fingers in the exact place for each note. A millimetre up or down the string produced disharmony, yet there are no guiding frets on a violin. I practiced as diligently as I could: open string bowing, scales, arpeggios, get that fourth finger in place ahead of time! I got my teacher to give me a mock exam during lesson time. It was humiliating. The week before the exam, my pieces were running on a constant loop in my head. I practiced my fingering while I slept, when I slept, which was seldom and badly. I practiced maniacally. I worked out every kink in continual mock Zoom exams, doubling down on the bits I flunked. Rory, the bass player, over to play in the Wednesday jazz trio at our place, asked whether I had ever played in front of an audience, incredulous that I would be doing a violin exam. Well, my in-laws, I said shakily, and I am a professor with a lifetime of public speaking behind me. Yeah, well this is different, he said, looking at me with concerned amazement. This was not confidence building. Two days before the exam, I felt that I had now learned the elements of preparatory violin, and performance of these basics was up to the vicissitudes of exam performance where, of course, anything can happen. I had memorized my repertoire pieces and, though not necessary, my étude as well. My scales were on autopilot. I felt that it was essential to credit myself with accomplishment of this basic learning and damn the torpedoes. I was ready for the exam. The morning of the exam, I ran around in circles preparing: my violin needed to be acclimatized to the humidity of the basement. I needed to ensure that the piano and the violin were exactly in pitch. Was there enough rosin on the bow? David and I practiced our simultaneous piano and violin start: an audible breath, really a sniff, and tally ho. I entered the zoom waiting room nervously. We were being recorded though no one was there. I thought I would wet my pants waiting for the zoom examiner to show up. And suddenly there she was with a friendly face. I silently thanked the heavens above that I had been spared a hangman, and greeted her so exuberantly, she must have thought me a little simple. I started by playing open strings just so we could adjust any controls on our respective technological connections for best sound and to check that my instrument was in tune. All the same, my fingers trembled, my sweat glands went into overdrive, and I forgot how to breathe. I did remember to smile and to play with the conviction my teacher had taught me to show. There were to be no faces pulled, indicating disappointment or frustration, and if I made a booboo, I was to make it with pride and move on. I began with my scales, and true to practice, practice, practice, they rolled off just fine. My étude began a little flat but it had spirit. My teacher had told me to sing my repertoire piece, entitled (appropriately), Song, to make up words, create a story and tell it in music. She told me to play what I heard in my head not what I produced with my fingers. So I did. My fast piece, the last in my program, was intended to be humorous, and it flowed with sheer relief. Whew! Then, adrenaline draining, I started to fade. I managed the ear training tests but goofed on one of my playbacks, exacerbating the mistake by apologizing and misnaming the note I had missed. The examiner smiled gently and thanked me for playing for her. The whole thing had lasted about 7 minutes. I regained my composure and my blood pressure slowly receded from the stroke zone as the morning wore on, though the excitement of the exam had been surprising. Later in the day I presented the annual review of our faculty’s innovative research intensification strategies to the Council of Associate Deans of Research across my university. In comparison, it was a cakewalk. In celebration, I bought the level 1 violin books and listened to all the pieces in the repertoire book. It was a week or two later when I got my assessment. I had indeed lost a point on my playback. Oh well. I had learned everything from memory (not a significant effort when all pieces are one page long) so I got full marks for that. The examiner was very generous in her assessment of my pitch and dynamics, and the work cut out for me was in relaxing my wrists and connecting the bow a little more solidly on the string. I had passed. Her commentary was clearly positive, though somewhat opaque to me as a rookie: “There is a very sweet tone colour here…Glissando is well attempted.” I kind of got the gist. But the mark surprised both of us… This will help you play in time. (1) talking metronome - YouTube You can easily search the tempo and time signature you need. The 1st collection counts in quarter notes, the 2nd in 8th notes, and the 3rd in 16ths. Other time signatures can be found on their YouTube channels. |

You've got to learn your instrument. Then, you practice, practice, practice. And then, when you finally get up there on the bandstand, forget all that and just wail. AuthorI'm a professional pianist and music educator in West Toronto Ontario. I'm also a devoted percussionist and drum teacher. Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed