|

It goes without saying that David is an accomplished musician on several instruments. I found him to be an excellent and responsive teacher as well. I started off thinking I would reconnect with the piano through lessons, but quickly discovered that my heart was no longer in playing a solo instrument. I asked David if he would help me with ear training instead, as I am singing in several amateur choirs. Although he was clear that he is not a voice coach, he has an excellent ear and agreed to this change in direction. He came to each session prepared with something new to work with, including some apps I could use on my phone to build my skills. He created an environment in which I felt comfortable to sing alone and make mistakes. We used my choir materials to explore some theory concepts, but he also surprised me with his own exercises. In the end, I feel more confident. I grew musically with his help and encouragement. His tutelage will allow me to enjoy my choir singing more. Thank you David!

NL MacDonald 2024 Thank you, Nona.

0 Comments

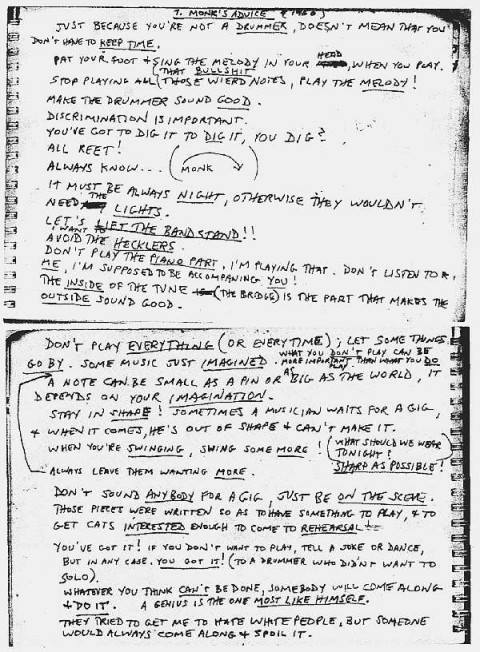

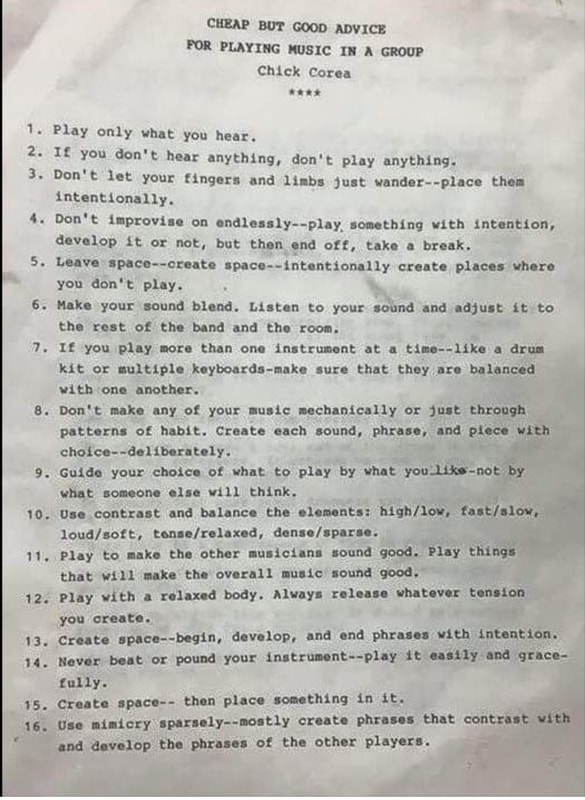

When all is said and done there are only a few simple steps one needs to follow. Of course, this means simple to describe and a lifetime to master.

Another perspective from Louis Armstrong. A Perspective that works every time. 1. Memorize the melody. 2. Mess with the melody. 3. Mess with the mess. If I can help you, call me. David Books and Websites on deliberate practice

Happy Practicing. David 1. Deliberate practice

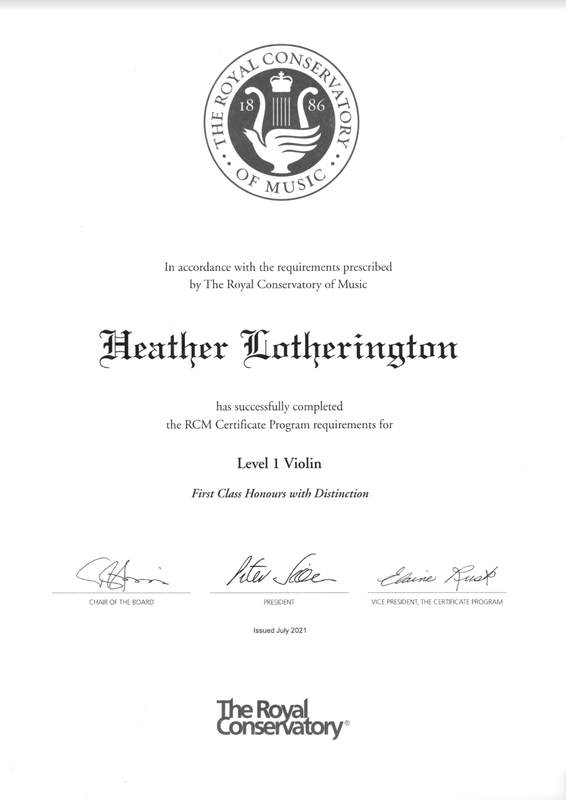

I have always listened to classical music, which I have loved since I was a child. My father listened to opera; he loved Beethoven. He knew nothing more than he liked this music and I never thought to ask him how he had met it in Sydney, Nova Scotia, growing up in the great depression on the wrong side of town. Growing up in the Maritimes I was also exposed to fiddle music as a fundamental feature of Maritime culture. And, of course, my coming of age coincided with the great folk festivals of the late 60s and the dynamic rock revolution of the 70s and 80s. Suffice to say, I have familiarity with a broad spectrum of musical genres. I progressed doggedly, passing my grade 1 examination, 7 months later (95). Playing before an examiner was, as Rory had voiced a couple of years ago, an intimidating experience. There is you and your violin and the marker and nowhere to hide. As a professor, I was used to making presentations before audiences of diverse sizes from a few people to hundreds. But I spoke about material that I had researched, taught, and written about as an expert in my field. I supported my talks with fancy, attention grabbing multimedia. I got to stand behind a lectern. I was never as exposed as I was playing the violin for an audience. Just playing for my teacher could make me break out in a cold sweat. But music is meant to be played with and for others, so performance is an essential skill. I had to practice performance as well the many physical skills intrinsic to playing a musical instrument. When I visited family in the Maritimes, I played for my mother in hospital (woe betide anyone else trapped in the same room). My brother would groan. My sister would praise my efforts, and acidly remark that no other 60 year old in the family seemed to be learning anything quite so difficult. My 90 year old mother would ignore her sniping children and merrily sing along. So would my daughter, in support of her grandmother slowly fading with dementia. I accumulated tunes I picked out by ear that mom could still sing: Frère Jacques, Row, row, row your boat, Old MacDonald had a farm and suchlike. I sent a tune a week to my sister (mom’s caretaker) to play to her. This became my weekly learning-by-ear project. On trips to visit David’s parents, both musicians, we gave concerts. Playing with David made me sound so much better. My father-in-law, a cello player and a choir singer with a practiced ear made the suggestion that I sing along to my playing for a check on pitch fidelity. Though I am not sure my singing is any kind of asset, singing in your head really helps to hone pitch, a necessity in playing any unfretted stringed instrument. It was a good call. The term “deliberate practice” I was familiar with, but it wasn’t until my list of scales and études grew too onerous to plow through daily that I had to schedule what I could and should do on a given day. This reshaped my practice, which by that point had grown from a half hour to 45 minutes stretching into an hour daily. I had to choose scales matching the requirements of the études and repertoire pieces, and make sure that I managed to do everything over the course of a couple of days. By the time I reached level 4, I had a grid outlining four days of technical studies: scales, arpeggios, double stops, which themselves followed left hand and bow warm-ups and preceded études and a selected repertoire pieces. Within each section, I had specific practice points. The job was to try to focus on one thing at a time—dynamics, pitch, expression, slow bowing, clean string crossing, and more, though I had to be responsible for everything in the end. Violin learning is intensely physical as well as cognitively demanding and aesthetically challenging. Practice is complex. I have remained with the same teacher, an excellent critic, demanding of attention to details and a seemingly endless font of advice on how to do sometimes minute things that contribute to violin playing. She is a concert violinist, who teaches. Now retired, I can be flexible with her timing, but I am constant. Even on weeks when I feel I have acquired absolutely nothing in practice, we have our lesson. Sometimes it is highly informative. Sometimes I feel like a four year old who can’t tie my own shoelaces. Always it is a learning experience. Nine months following my Level 1 exam, I passed Level 2, (88), and a year after that, Level 3 (87). Lucia was frank: the period of preparation gets longer with each level and the marks slide with the increasing level of complexity. I am hoping to be ready for my Level 4 exam in a month or two and have extended my preparation accordingly. Lucia says, there is no hurry. I now practice once or twice a day for an hour to an hour and a half. I stretch and roll out tight muscles to keep as much fluidity as possible playing an instrument infamous for causing neck and back pain. Five years after that first birthday gift of a rental violin, I treated myself to a handmade carbon fibre violin that I fell in love with. I have upgraded my wooden violin and acquired two quality bows: a carbon fibre for fiddle music, and a pernambuco wooden bow for best tone in classical music. The idea that I might stop playing is now ludicrous—this is an immense journey and I have got this far. There is no turning back! My teacher says, you can become a doctor in 7 or 8 years, but it takes a lifetime to become a musician. I still resist beginning my practice some days when listening to myself is depressing, though less so than in the early days, when dogged repetition was required to get anywhere at all. I now also take fiddle classes in addition and sometimes play fiddle tunes with friends who are more advanced but gracious and tolerant. Come to think of it, my pitch is better than some of the other fiddlers who haven’t paid such close attention to detail as I have had to with private lessons. I am working on vibrato which I find fearfully difficult. Lucia reassures me. This is a long process. Just keep working every day and slowly, there will be progress. Heather Lotherington 1. Committing to the instrument!

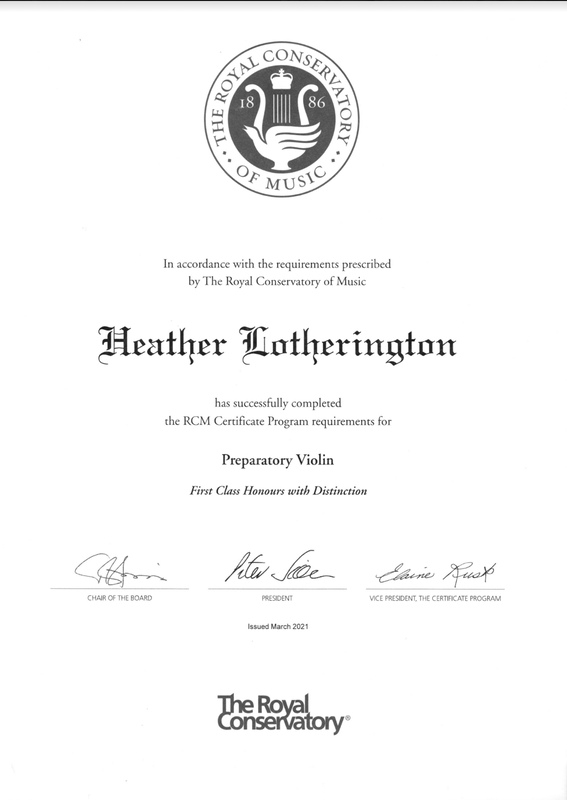

I made the first of my solid commitments to learning to play the violin in the early months of my learning journey (before the beginning of the pandemic) when I returned my inexpensive rental instrument to Long & McQuade, and went to The Sound Post to buy my very own violin. Terrified to showcase my elementary playing skills, I asked the salesclerk to play the array of violins he had picked out that were within my price range. This he gladly did—perhaps not for the first time, I thought. After all, a sale is a sale. Buying a stringed instrument and/or a bow carries a trial period. My teacher, Lucia, had made it very clear that I would need to play a new instrument for a while to know if it felt right. My criteria for feeling right were rather slim at this stage, so I chose the most resonant violin complete with case and bow, and just looked at it for a while when I got it home. It was a lovely student violin and it got me through the first few years of learning. My problems at this stage of learning—level 1—were myriad: I had insufficient strength in my fingers (to hold down the strings) and back (to hold up the bow without tension) and lacked the requisite flexibility in my shoulders, arms, hands and wrists to reach all the notes on a violin. My joints slowly opened up as I strove to reach hard to hit notes and press hard enough on the string to make a good sound—or maybe any sound. But this did not happen overnight, and trying too hard just caused more stress injuries. Listening to myself was still unutterably dismal and horribly demotivating but I just kept pushing through on blind faith. When I received the final mark on my embossed RCM assessment for the preparatory level, I wondered for a moment, if they might have sent the result to the wrong person. 91? First class honours with distinction? I was amazed! With this positive reinforcement, I launched headfirst into Level 1. On the technical side, I graduated to A minor harmonic (check!) and A minor melodic, which was a scale I had never heard of before. The dreaded C major scale made an appearance. I also had G major—on two octaves. There would no longer be any excuse for avoiding the G string. Not only did I have to learn the G scale starting on the open string, the lowest note on a violin, but the C scale began on the G string with the third finger. No tonal reference point. Tricky! There were also double stops: playing two strings at the same time. These were open strings: perfect fifths. They sounded beautiful but it was devilishly difficult to balance on both and keep the hee-haw sounds down. Turning the page to the études, I saw a definite escalation. My studies included pieces with accidentals, double stops, harmonics, slurs over four notes (oh come on!) and sixteenth notes, though fortunately not altogether in the same place. They presented a kind of choose your poison smörgåsbord. I sat, listened and read along to every piece in the repertoire book, all played by professional violinists who sounded hopelessly perfect and beautiful. I tried to judge the most doable pieces for myself. These were not necessarily the easiest, but I did not want pieces deliberately pushing the boundaries of the next level. Showboating is for young people with good joints and easy flexibility, who also play on proportionately smaller violins. No such luck for seniors. I listened for something else, too: I wanted to play what I liked. There was a wide variety of pieces offered, so this was not hard. I met composers, such as Dmitri Kabalevsky, whose compositions I loved, and found traditional songs, such as, Un Canadien errant, a beautiful, haunting piece that I have known since childhood. I found a lovely ballad written as a duet, and asked Lucia to record the second violin. When she sent it and I played along, magic happened. Playing against a beautifully performed second violin made my first violin part sound so much richer. I played and played that piece. I still play it years later to practice more advanced techniques, such as vibrato. Cycling back to earlier pieces to practice new skills, coincidentally a feature of the Suzuki method, was reassuring and affirming of my progress. Thus far, I had organized my daily practice in terms of a linear run through the technical exercises, studies (now two of them) and selected repertoire pieces. Though still generally useful as an organizing principle, linear study was becoming physically unrealistic. I needed to learn to do deliberate practice. 1. My (heart-attack inducing) preparatory violin examination

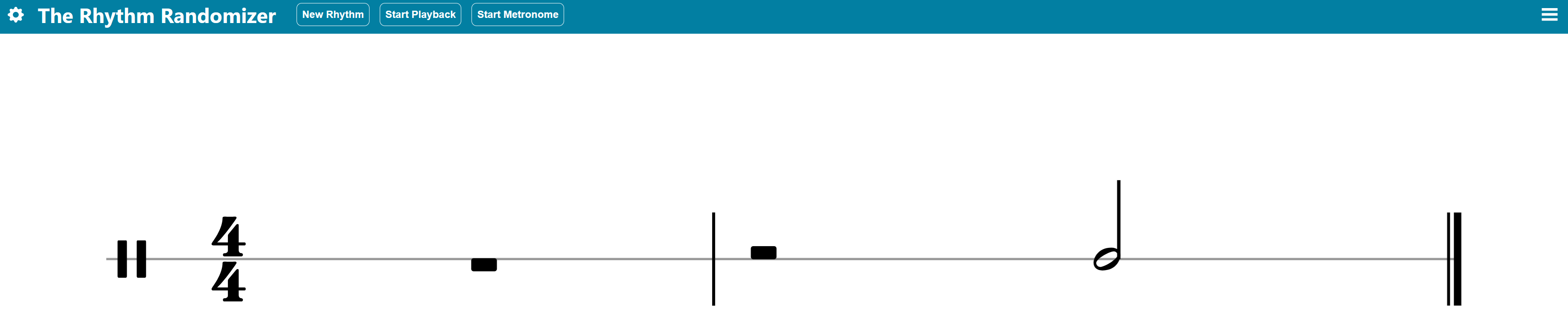

When my teacher, Lucia, thought I was ready for the examination, about 6 months in, I nervously opened the appropriate account on RCM and applied for an examination date and time, choosing a time when my playing would not disrupt any of David’s regularly scheduled musical activities and he could accompany me on the two repertoire pieces. I chose 9:30 am, giving me enough time to wake up, eat, warm up, and—recommended by Lucia—retune my violin to the conditions of the basement where the zoom exam would be held. A month before the examination my nerves started getting the better of me, so I intensified my practice time on the weekends, bearing down on my scales and arpeggios, determined to get my fingers in the exact place for each note. A millimetre up or down the string produced disharmony, yet there are no guiding frets on a violin. I practiced as diligently as I could: open string bowing, scales, arpeggios, get that fourth finger in place ahead of time! I got my teacher to give me a mock exam during lesson time. It was humiliating. The week before the exam, my pieces were running on a constant loop in my head. I practiced my fingering while I slept, when I slept, which was seldom and badly. I practiced maniacally. I worked out every kink in continual mock Zoom exams, doubling down on the bits I flunked. Rory, the bass player, over to play in the Wednesday jazz trio at our place, asked whether I had ever played in front of an audience, incredulous that I would be doing a violin exam. Well, my in-laws, I said shakily, and I am a professor with a lifetime of public speaking behind me. Yeah, well this is different, he said, looking at me with concerned amazement. This was not confidence building. Two days before the exam, I felt that I had now learned the elements of preparatory violin, and performance of these basics was up to the vicissitudes of exam performance where, of course, anything can happen. I had memorized my repertoire pieces and, though not necessary, my étude as well. My scales were on autopilot. I felt that it was essential to credit myself with accomplishment of this basic learning and damn the torpedoes. I was ready for the exam. The morning of the exam, I ran around in circles preparing: my violin needed to be acclimatized to the humidity of the basement. I needed to ensure that the piano and the violin were exactly in pitch. Was there enough rosin on the bow? David and I practiced our simultaneous piano and violin start: an audible breath, really a sniff, and tally ho. I entered the zoom waiting room nervously. We were being recorded though no one was there. I thought I would wet my pants waiting for the zoom examiner to show up. And suddenly there she was with a friendly face. I silently thanked the heavens above that I had been spared a hangman, and greeted her so exuberantly, she must have thought me a little simple. I started by playing open strings just so we could adjust any controls on our respective technological connections for best sound and to check that my instrument was in tune. All the same, my fingers trembled, my sweat glands went into overdrive, and I forgot how to breathe. I did remember to smile and to play with the conviction my teacher had taught me to show. There were to be no faces pulled, indicating disappointment or frustration, and if I made a booboo, I was to make it with pride and move on. I began with my scales, and true to practice, practice, practice, they rolled off just fine. My étude began a little flat but it had spirit. My teacher had told me to sing my repertoire piece, entitled (appropriately), Song, to make up words, create a story and tell it in music. She told me to play what I heard in my head not what I produced with my fingers. So I did. My fast piece, the last in my program, was intended to be humorous, and it flowed with sheer relief. Whew! Then, adrenaline draining, I started to fade. I managed the ear training tests but goofed on one of my playbacks, exacerbating the mistake by apologizing and misnaming the note I had missed. The examiner smiled gently and thanked me for playing for her. The whole thing had lasted about 7 minutes. I regained my composure and my blood pressure slowly receded from the stroke zone as the morning wore on, though the excitement of the exam had been surprising. Later in the day I presented the annual review of our faculty’s innovative research intensification strategies to the Council of Associate Deans of Research across my university. In comparison, it was a cakewalk. In celebration, I bought the level 1 violin books and listened to all the pieces in the repertoire book. It was a week or two later when I got my assessment. I had indeed lost a point on my playback. Oh well. I had learned everything from memory (not a significant effort when all pieces are one page long) so I got full marks for that. The examiner was very generous in her assessment of my pitch and dynamics, and the work cut out for me was in relaxing my wrists and connecting the bow a little more solidly on the string. I had passed. Her commentary was clearly positive, though somewhat opaque to me as a rookie: “There is a very sweet tone colour here…Glissando is well attempted.” I kind of got the gist. But the mark surprised both of us… This will help you play in time. (1) talking metronome - YouTube You can easily search the tempo and time signature you need. The 1st collection counts in quarter notes, the 2nd in 8th notes, and the 3rd in 16ths. Other time signatures can be found on their YouTube channels. 1. Preparatory violin study

Lucia, my violin teacher, who I had not seen in months, approached me online in the spring of 2020 when we were all hunkering down for what would be a couple of years, though none of us knew that then. She suggested I start up my violin lessons again on zoom. Lacking distractions from work (in my home office), I thought, “why not?” But this time I would take a more systematic approach. I would take David’s advice and follow the RCM program to put structure into my learning. Lucia thought this was a stellar idea, and so I bought the RCM Preparatory Violin books: technical study and repertoire, keen to crank up again on a clearly defined path. Looking through the books, though, I became fearful: this was preparatory? It was hard! Worse still, the preparatory technique book spanned from preparatory to grade four; sneaking a peak ahead was the stuff of nightmares: notes all over the place, doodads over the notes, fancy scales under long phrase lines and all nature of scary stuff. I should come clean and admit that I studied piano as a child (early Pleistocene era), so I was not musically illiterate. The six years I spent learning to play the piano with French Canadian nuns (tough task masters) included theory and, helpfully, solfège, which I was to meet again, unexpectedly, in fiddle class a little further down the track. But the system at Notre Dame D’Acadie was organized differently from RCM programs so I could not say what grade I reached. Nonetheless, not having to learn theory and sight reading from a standing start was helpful: the cognitive load in reading music and playing it at the same time is significant and should not be underestimated. All the same, I had to see the notes on the page as points on a violin string. This was new. I could picture, say middle C (along with the scales, arpeggios, etc.) on a piano but I had to find it on the violin and hear it and feel it in my hand, so I wasn’t (desperately and unrecognizably) off pitch. Preparatory began sensibly with the A major scale, the most basic scale on a violin, played on the easiest string to reach. This was friendly. I knew what a major scale should sound like, so I could practice towards it sounding right. I could reach these notes, though they were kind of pesky to find. With the A major scale, I had the A major arpeggio over one octave. I had single bows only: one note, one bow. I could do this!!! I graduated to the D major scale. So exciting! By now I could reach the D string but going from the A string to the D string was harder than the other way around. And then, the D arpeggio. I was rocking. The études were another matter. On the first page was one in sixteenth notes going up the D scale but it had accented quarter notes in it and dynamic shifts, and… harmonics? What the hell? Where did these come from? My violin teacher admitted that she favoured the Suzuki approach to the RCM program, as RCM tended to erratic étude and repertoire choices and levels of difficulty varied even within a single level. But Suzuki was for children, I thought. Well, she explained, adults do it, too. It is oriented to ear-training. The downside is that Suzuki learners are not as strong at sight reading as RCM learners. At the time, I was senior faculty at a large urban university, seconded to a senior administrative post. I had to solve faculty problems and answer to university leaders throughout my day—all on Zoom—which limited my available practice time, and on some days, wiped me out past even starting the depressing regimen of hunt and peck scales. But motivated by a fear of making a total ass of myself in front of an examiner accustomed to 5 year olds capable of mastering this content, I pushed onwards. I stretched, I practiced, I recorded myself and self-critiqued. I watched superstar violinists on YouTube, and listened attentively, studying how they held their violins and their bows. I practiced with my husband playing the piano or the ukulele; I played to recorded tracks; I sent video-recordings to friends and family. Mostly they were encouraging, and not without incredulity that I would undertake such a project at my age. My daily practice was organized around a linear read of the technique and étude book, followed by my big moment: my repertoire pieces. Two! I felt practically ready for Carnegie Hall in comparison to where I was with Twinkle, twinkle little star a year ago. And as such, my practice was shaped as a daily scrum with my violin, progressing through each section of the preparatory course that I would have to perform for my examination, though the sightreading selections came later, as did the ear training. Ear tests I got from David, whose musical knowledge was immense, and patience, even more so. Most of the repertoire selections were sensibly scored in the keys of A and D but some joker had put in two pieces in the key of C major, which is NOT a friendly key on the violin. At least, not at this level. The pieces had names like Playing ball and Pony trot, which felt a little undignified for a mature woman. Nonetheless, I tried as many as I could manage and settled on a pretty lullaby called, evocatively, Song, and another rather quirky piece that was quite dramatic in character, called, The old jalopy, which had a cute slide at the end of it. I practiced these pieces till my fingers were raw, so keen was I not to make a total fool of myself on my debut examination. David and I practiced together once a week, he on the piano part provided in the repertoire book. From this, I got the bright idea to tape his part, so I could play along to it during my daily practice. The exemplars provided by RCM were all too fast, plus they were played by professional musicians with beautiful tone, vibrato, perfect intonation. Impossible models… Just fiddling around

1. Fiddle dee dee Heather Lotherington I took up the violin in my 60s. It was early summer, 2018, shortly after my daughter had taken me to task on a constant refrain that my next car would be a Porsche. On my birthday, she met me at a Porsche dealership and insisted the two of us test drive the car of my dreams. Midway out of the lot, the exquisite sports car’s battery went flat, and we drifted into traffic. It was horrifying—but a dramatic lesson. Life waits for no one. (I bought an Audi TT instead). When my husband suggested a lovely gift idea for my birthday, I declined and asked for violin lessons. Soon after, I had a rental violin in hand, and a month’s lessons lined up with a local teacher, who I found online. And thus began my violin journey. I remember my first lesson: I had no idea how to hold the violin or the bow or that I needed a shoulder stand to help position the violin more comfortably on my shoulder. I didn’t even know how to pick up my instrument. It was a very cold start. I reckoned that playing the violin—an idea in the back of my mind for some time—might help stem my arthritis and encourage some flexibility in my increasingly knobby, stiff fingers. This wasn’t the primary motivation for learning, but it did help to spur me along. I had put off my dream of playing the fiddle for long enough. If I didn’t get going, my hands were going to become inflexible claws. Plus, how hard could it be? The fiddle is commonly played by countryfolk by ear, and you see even little children wailing away on violins. Fast forward past the commitment of buying a violin and a sustained period of caterwauling that caught the attention of local tomcats, past the perpetual state of terror at lessons, a badly inflamed shoulder, unending frustration, and constant tweaking of violin, shoulder rest, chin rest, bow to find a position where my instrument felt even quasi-comfortable. It would be lovely to sugarcoat just how miserably trying this beginning period was. It was by sheer dogged determination that I survived. My bowing was crooked (it looked straight to me, but such is parallax), sliding towards the fingerboard, which created an awful tone. My bow (right) elbow was all over the map instead of steadily in position for the string being played, so I “string-crossed,” or hit more than one string at one time. This can be done by design; mine wasn’t. (Think donkey braying noises.) My bow bounced off the string when I lowered it to play. I could only reach the top two strings (E, A) with my left (violin) hand and I had absolutely no idea how violinists got all twisted around to reach much less play the D string and the bottom (G) string. My left shoulder and back ached to the point where I had to stop entirely for a few months and get physiotherapy to repair the tense, weak, underused muscles I needed to build. So, the first hurdles were painfully physical. My teacher, Lucia, was understanding. “No one is born playing the violin,” she would say. There was a learning curve just to holding the instrument. But there was also a focus hurdle. I wanted to learn to play the instrument, and my teacher did her best to guide me. On her advice, I bought a learner book. But my agenda was vague and unhurried. I would practice the same songs again and again, and sound just as bad as the last time I played them. I was mystified how violinists found the exact notes on an unfretted instrument when there seemed to be so much room for error. Practice was demotivating to say the least. After several months, I could feel my teacher’s impatience as she tried to move me ahead in my learner book to attempt a simple jig. I crumbled. I couldn’t tell where those high notes were and jumping up two strings from the D, which I could finally reach, was taxing. I would practice and hate every moment. And then Covid-19 hit and life came to a grinding halt. I stopped playing. Looking back, I now see two glaring problems I faced during that first unproductive period:

I was horribly disillusioned. Monitoring my increasing disheartenment at plowing through my beginner book, my husband made a sensible, informed suggestion: sign up for an examinable music program. So I did. Learning to play a musical instrument, even at an elementary level, is going to take effort and persistence. Any activity that helps you to maintain your enthusiasm should be welcomed. Here are five ways I assist myself. You might think up your own list.

Both programs and institutions were similar in size, scope, and intent. They had similar goals of producing professional musicians and skilled teachers.

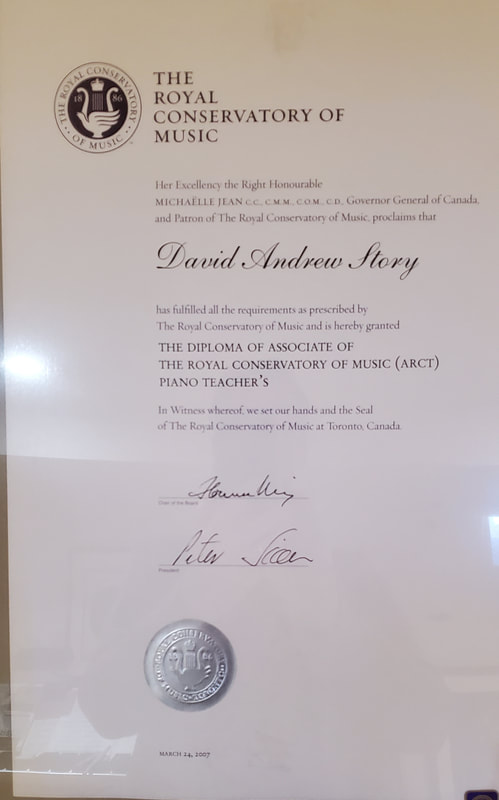

At Berklee I studied jazz composition, a creative and primarily cerebral affair. The music courses were interesting but not too challenging. In contrast, the Royal Conservatory of Music (RCM) was a full on physical experience that challenged my endurance, courage, and self-image. At Berklee I excelled easily because I came to the experience with considerable professional experience behind me. Classical piano on the other hand was a new disciplined practice that I had no experience or preparation for. A Berklee I was trained to be an employable musician and its skills still work. At Berklee, creative wondering was encouraged. This lead to all sorts of self indulgent activities. However, at the RCM I was challenged not to be "creative" but to be skilled and competent. At the RCM I decided for the first time in my educational life to simply follow directions, do what I was told, and see what happens. The result of all this obedience? I really learned how to play the piano beautifully and realise my potential both as a player and teacher. Being "creative" is easy if you use yourself as a reference for judging the output. But, playing beautifully according to independent assessment of a jury is not easy. So, Berklee was easy, the RCM not at all. If you would like help preparing for either experience, call me. David Zoom whiteboard notes from a piano student's lesson A student asked me questions on practicing. Do I practice every day, how long do I practice, when do I practice, what do I practice? How do I keep my enthusiasm for drumming year after year? Here are my answers.

As many people know, I took up the drums at age 50 after an adult student challenged me by saying I had no idea how difficult it was to learn as an older adult. I took the challenge. So, this blog is about my percussion practicing. (When my musical colleagues ask why I started drumming I tell a more colourful story that involves my misperception that drumming would be a cheaper mid-life crisis solution than buying a red sports car.)

If I can help and encourage you on your musical journey, call me. David aka "sticks Story" PS. I now cart my drums around in a red Cadillac. Not quite a sports car, but more drummer friendly. How much practice, time, and effort did earning my Royal Conservatory Level 10 and ARCT Pedagogy diploma take?

Fanny Waterman was a legendary piano teacher in the UK who died in 2020 at the age of hundred. She was big on rules in the piano studio. My responses are lettered.

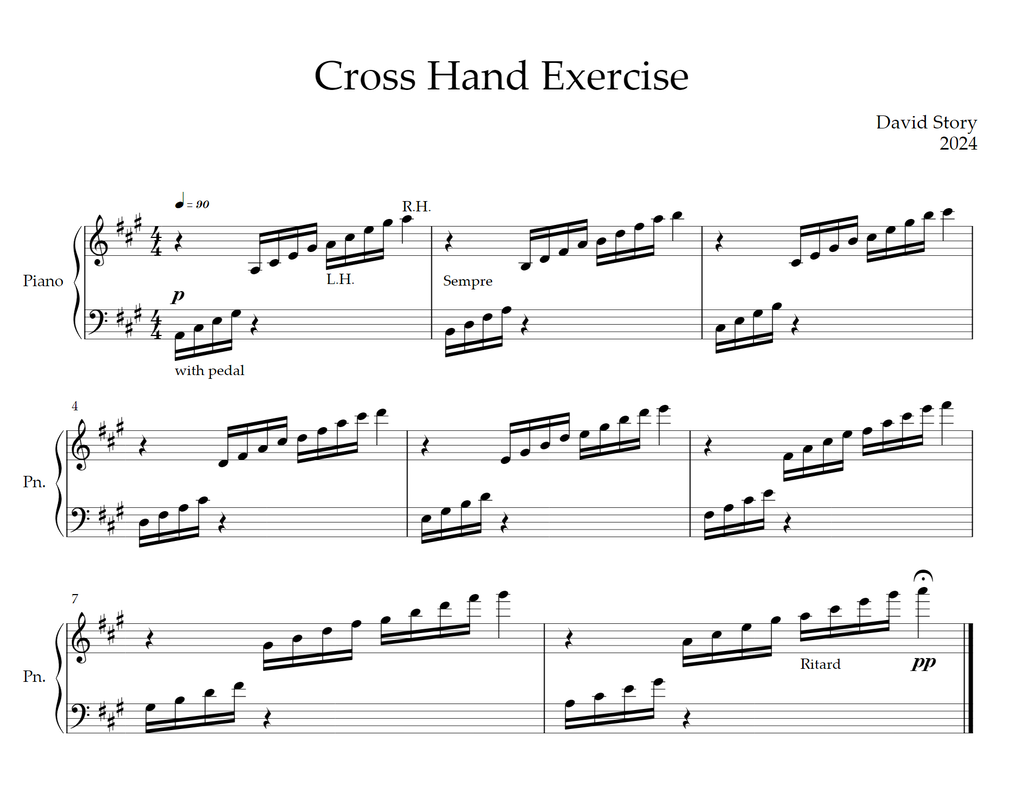

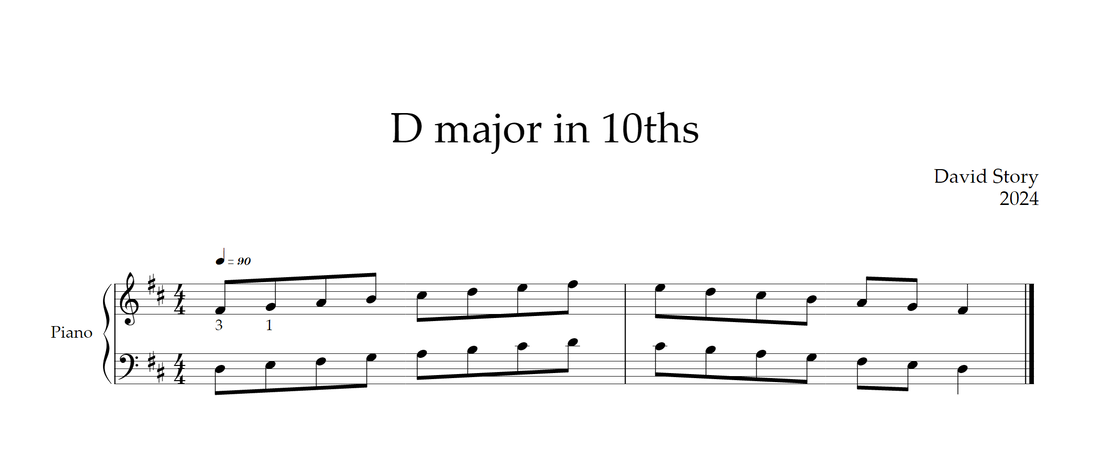

The following ten practice rules are modified from her book. 1. Sit straight with your fingers rounded. 2. Practice each day. a. Ms. Waterman lived in a simpler time. However, without regular practice, progress is difficult. Therefore, it is important that the student’s practice time is aligned with their ambitions and goals. 3. Before practicing new pieces, clap and count aloud the rhythms within. a. Use a metronome to keep your counting honest. 4. Write in the appropriate fingering and then stick to it. Different hands will require different solutions. a. Begin by following the fingering given. 5. Begin a new piece hands separately, then hands together. 6. Play slow enough to eliminate or minimize errors. a. In my own practice I note the tempo that I play without making errors. Each practice I begin at this tempo. Over time the music will speed up with minimal errors. 7. Master the rhythm before adding rubato and other rhythmic variations. 8. Never play through a mistake. Stop and correct it and then correctly repeat it numerous times before proceeding. 9. Pay attention to and fully understand the meaning of all the markings and text in the score. 10. Listen to how you sound. a. Self-assessment is difficult. Recording yourself is your best chance of accurate self-assessment. I have 15 years of drum practice recordings on my hard drive. (No kidding) I also practice in front of a mirror to check my posture. Fanny Waterman pg. 10-11, 1983 Note what is missing. There is no mention of listening to professionals play your pieces before you begin. This is my new rule. Listen and listen often. Know every note by heart. If I can help you, call me. David I've been playing scales for over 50 years so keeping it fresh can be a challenge. This etude was written for an intermediate student today. Playing scales at the 10th made it all new for her again. Feel free to try this with other scales as well. Keywords: Scales, scales in 10ths

Kind and Wicked Learning Environments in musical study.

The subject of kind and wicked learning environments is a complex subject. This blog deals with just a small application of the insights of researchers. Namely, the use of feedback to make correct decisions. For deeper details, there are links in the Psychology today blog to the research papers and scholarly books. Definition: In a “kind” learning environment we learn from experience. For example, in sports we get immediate feedback because the distance between cause and effect is immediate. Furthermore, with help from the coaches, teammates, and others we progress through the predictable steps to mastery. Musical proficiency is similar. But, in “wicked” learning environments there is, for many reasons, no predictable path to mastery. This blog will only discuss the “kind” learning environment and the role of feedback. Feedback is crucial to learning a musical instrument. The popular late 20c. axiom, “feedback is the breakfast of champions” incapsulates this idea. Creating feedback loops in your practice is key to progressing with fewer setbacks and false starts. While in lessons the teacher provides immediate feedback, at home we are left to our own devices. Here are a few strategies skilled music students use at home.

The links below go to science. Psychology today has a list of scientific papers and links. If I can help you on your journey, call me. David References: Experience: Kind vs. Wicked | Psychology Today How to give and receive feedback effectively - PMC (nih.gov) The six skills of pianists

I don’t believe in talent. In my experience, all the so-called talented people turned out to be the hardest working, patient, and focused people of any cohort. However, they also had access to resources, like time and money to support their journey. Fortunately, there is a consensus around the core curriculum and its proper sequencing in formal piano studies.

If I can help you on your journey, call me. David Revised 2024 I take lessons and play in several musical groups. Only one group needs serious practice of specific pieces outside of rehearsals. However, all the groups are populated with active and retired professional musicians, like me, who expect that I will show up ready to play. Furthermore, the teacher I work with expects me to show up prepared. Some weeks I'm given a dozen pieces to learn. This is how I manage. I divide the pieces into two piles. The first pile consists of the pieces I can sightread. I never practice these. The second pile is divided into two further piles: the easy pile which consists of pieces that have passages that need the once over and the difficult pile that causes panic. I quickly dispatch the easy pile. In preparation for tackling the difficult pieces I repeatably listen to professional recordings of the pieces to have a clear aural understanding of the part. I then tackle the difficult stuff as follows.

Because I've prepared properly my heart is not conflicted. I'm at peace with whatever happens because I have done all that is humanly possible. However, sometimes, life gets in the way, and I will show up less than prepared. Then the banked musical skills of half a century kick in. You may not have half a century of experience to lean into, but as time goes by you will. If I can help you learn to practice, call me. David Revised 2024 I taught my first piano student in 1982.I can still remember the song I taught them to play. "Wake me up before you go go" by Wham. They were thrilled. What have I learned in the intervening years on student success? Plenty. Here are a few understandings about learning successful students have. 1. It takes years to acquire any sort of mastery. Learning piano is a ladder one climbs year after year after year. However, if your goal is to plunk out simple melodies and play some chords the road is not so long. Most students have ambitions somewhere in between. 2. Successful students enjoy every part of the journey: technique, aural skills, etudes, repertoire development and retention, sightreading, theory, and playing with others from time to time. 3. To take up the piano in adulthood, one will have to give something up to make room for it. 4. Students preparing for post-secondary music studies must have full parental support and encouragement. 5. Students preparing for post-secondary music studies must have Olympian levels of commitment and determination to their project. 6. It is never too late to start. If I can help you on your journey, call me. David PS. I took up the drums at age 50. Fourteen years later I now play, twice a week or more, in different groups that I'm proud to invite students to hear. For more stories on learning music as an adult click on these links: Piano lessons site:www.theguardian.com or adult music lessons site:www.theguardian.com

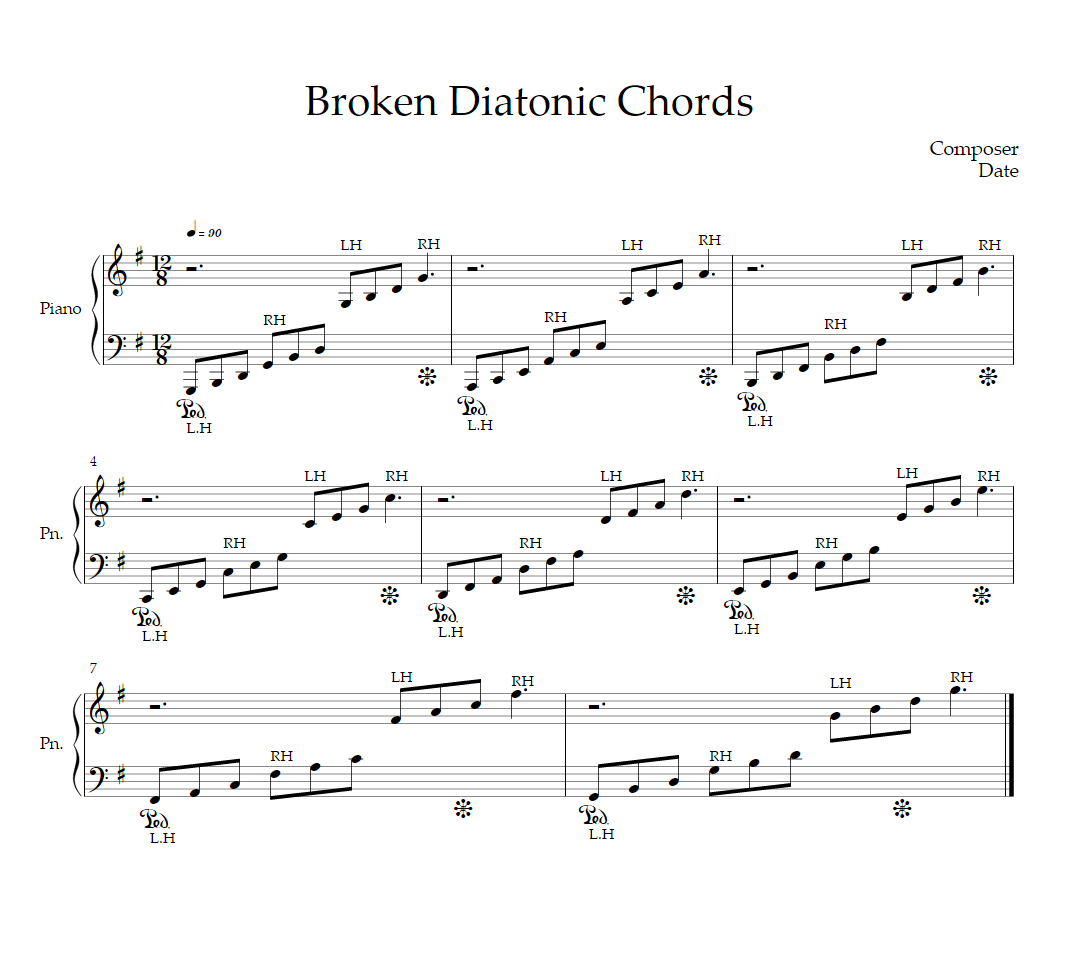

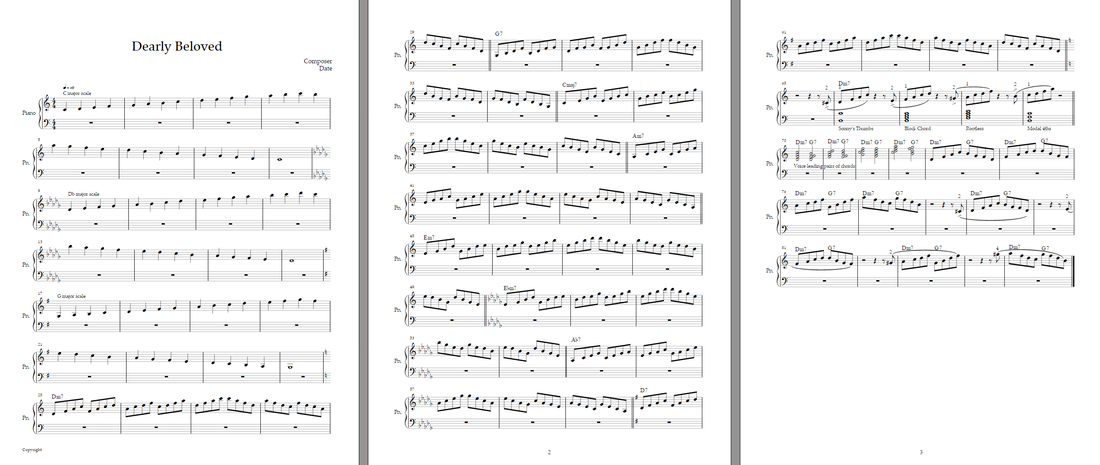

Here is a lesson I gave a student today. The student is not a beginner, but a happy amateur who learned to play jazz in his 70s and now in his 80s plays each week in a jazz band. Beginning improvisors need to prepare the harmonic and melodic elements before they commence. I suggest the following exercise to him. 1. Listen to multiple recordings of the piece. 2. Mark in the ii-V-I progressions and identify the keys they are associated with. 3. Practice the major and natural minor scales associated with those keys. 4. Practice the broken chords in the right hand. 5. Practice voice leading the chords in the right hand as shown at measure 70. 6. Practice linking them together in 8th note melodies as shown at measure 75. 7. Practice with chromatic approach notes before the 1st chord tone as shown at measure 79.

Have fun. David Sightsinging, Aural Skills (aka ear training), Sight reading, Memorisation, and Musical Competency12/11/2023 There is a relationship between sight singing, aural skills, sight reading, theory, memorization, theory, music history, and musical competency. Undergraduate musical programs have strengthened these skills and demonstrated the clear relationship between them and musical competency for hundreds of years.

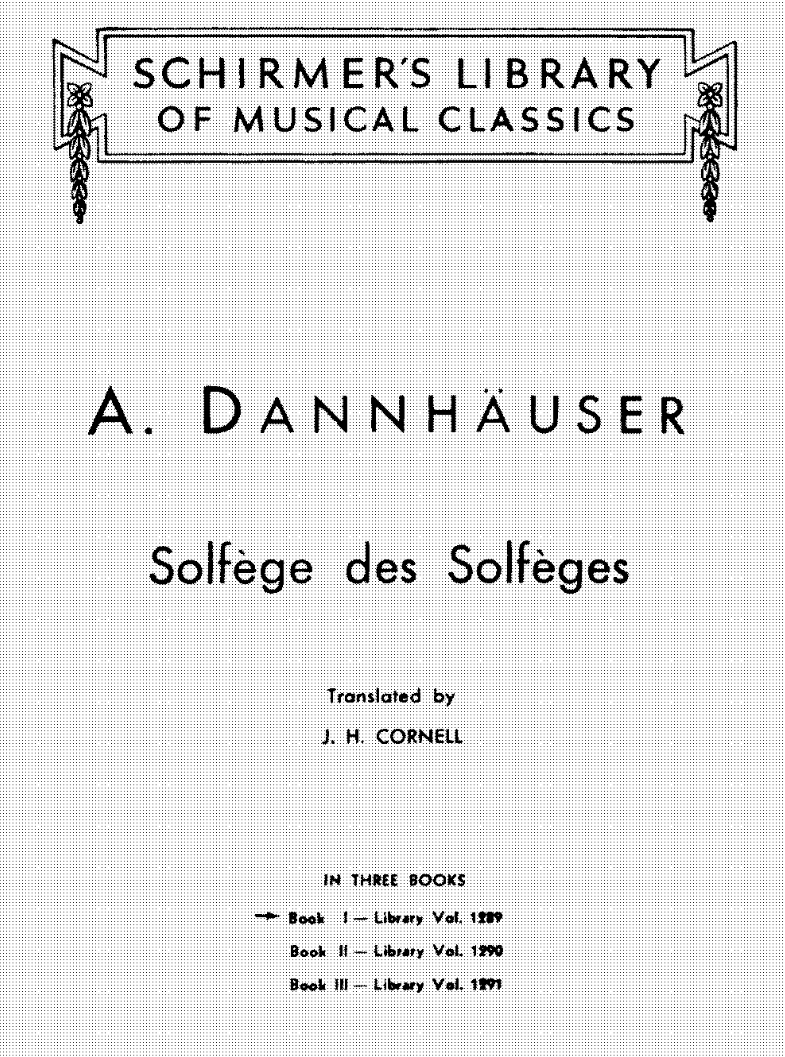

Clearly, studying with a music teacher such as I will not take the place of undergraduate study. However, I can prepare the student for those studies. And more importantly however, I can help strengthen those skills in my adult hobbyist musicians. Programs such as the Royal Conservatory of Music (RCM), and the Faber's series called Piano Adventures, and others, have well thought out curriculums, in a logical order, that cover all these important areas. The pictures below have links their content. All the information is free and does not require registration etc. However, some, but not all, will require you to purchase them at your local store. I do not take a commission from any sale. If I can help you, call me. David Learning new pieces quickly and efficiently is the goal of every musician. For example, I play in a musical group that requires me to learn pieces very quickly. Plus, I'm a busy guy who has no time to waste on inefficient practice. So, I've learned to practice with results in mind.

My advice today is based on the following premises. Premise 1: Slow practice saves time. Premise 2: Practicing hands separately saves time. Premise 3: Consistent fingering brings confidence in performance. 1. Listen to the recording to the point where you can sing along or at least be able to recognize a wrong note in your playing. Too many students play a wrong note for an entire week because they are unfamiliar with the sound of the music. This will also help your rhythm, expression, dynamics, and articulation. 2. Whenever possible, pick editions that have editorial fingerings. Unless there is a good reason to change a fingering in the score, don't. Next, take the time to fill in the missing fingerings between the ones the editor has given. This will save you time because you will have to think through and play each note in its proper sequence. If there are no fingerings given, take the time to work out the fingering for the piece and notate them in the score. Now you are thinking, experimenting, and practicing at a very slow tempo with your mind and hands fully engaged in the task at hand. This is an excellent use of your time. 3. Stick with it. 4. Practice in small chunks. If I can help you, call me. David It's that time of the year. Have fun!

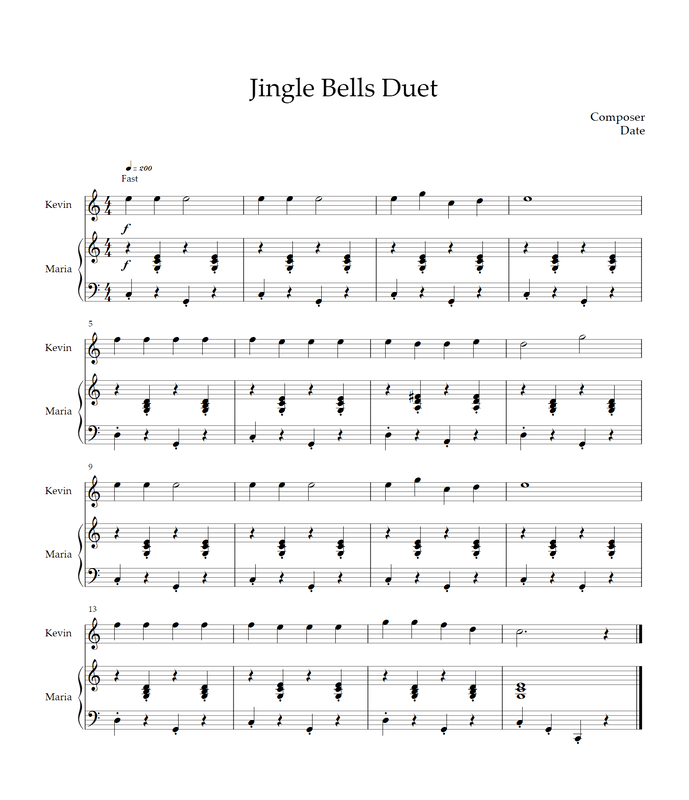

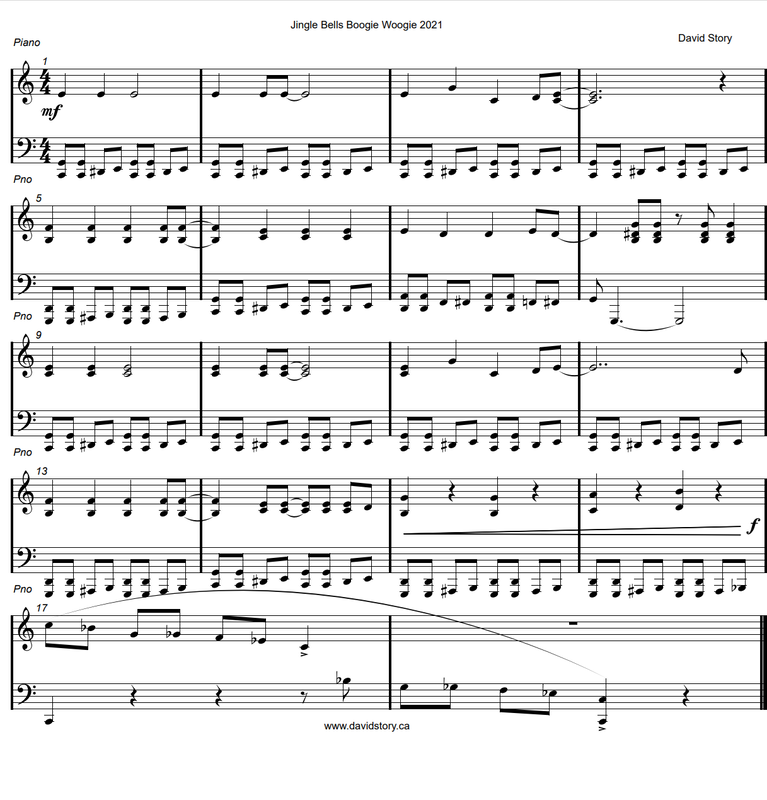

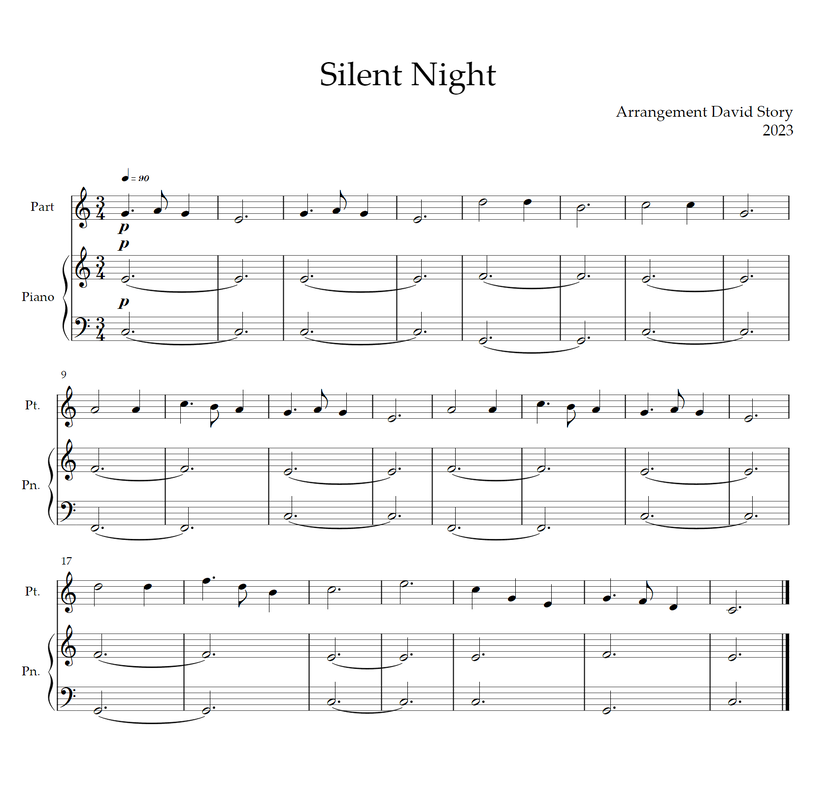

1. Jingle Bells 3 hand piano duet with free downloadable score. 2. Jingle Bells boogie woogie for solo piano with free downloadable score. 3. Silent Night 3 hand piano duet with free downloadable score. My scores do not require registration. David |

You've got to learn your instrument. Then, you practice, practice, practice. And then, when you finally get up there on the bandstand, forget all that and just wail. AuthorI'm a professional pianist and music educator in West Toronto Ontario. I'm also a devoted percussionist and drum teacher. Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed