|

This was discussed yesterday in class with a student who is a bass playing retiree. He is not a beginner. I'm his jazz teacher. We compared notes on what to practice by comparing what he is currently doing with my suggestions. He started us off.

Student: Jazz Practice session

Teacher: Music practice suggestions.

If I can help you, please call me. - David Story, Online Piano Lessons from Toronto

0 Comments

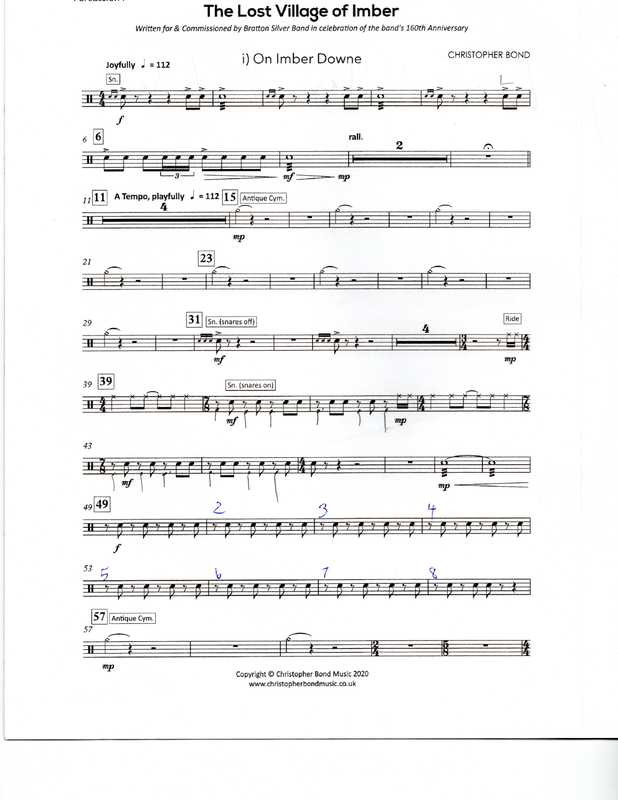

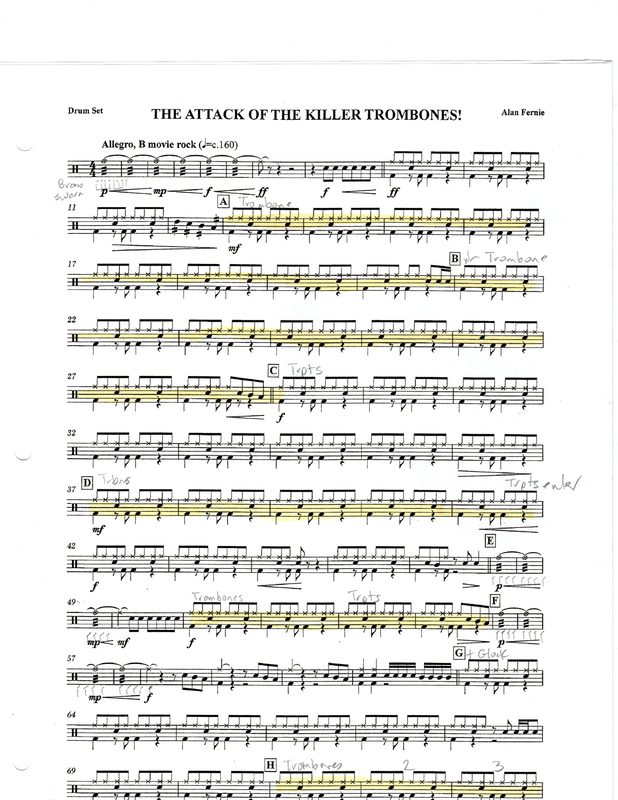

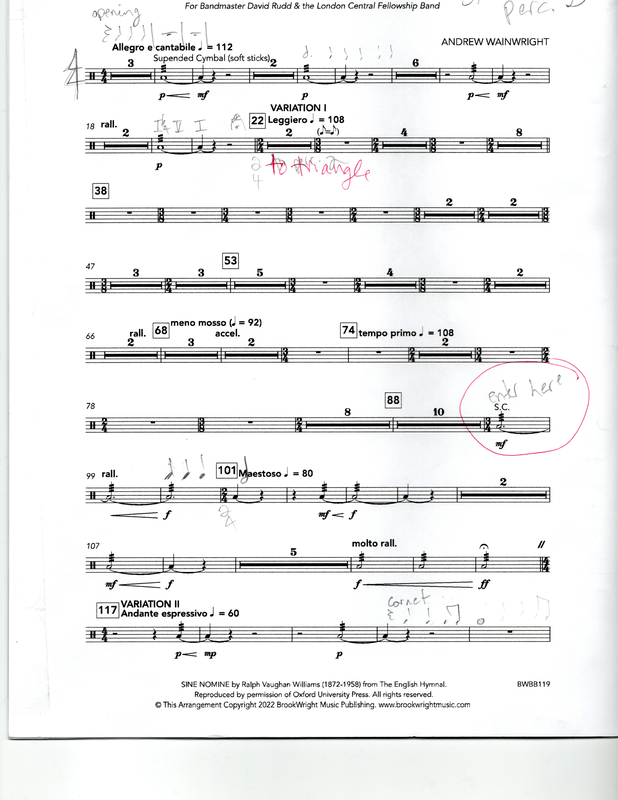

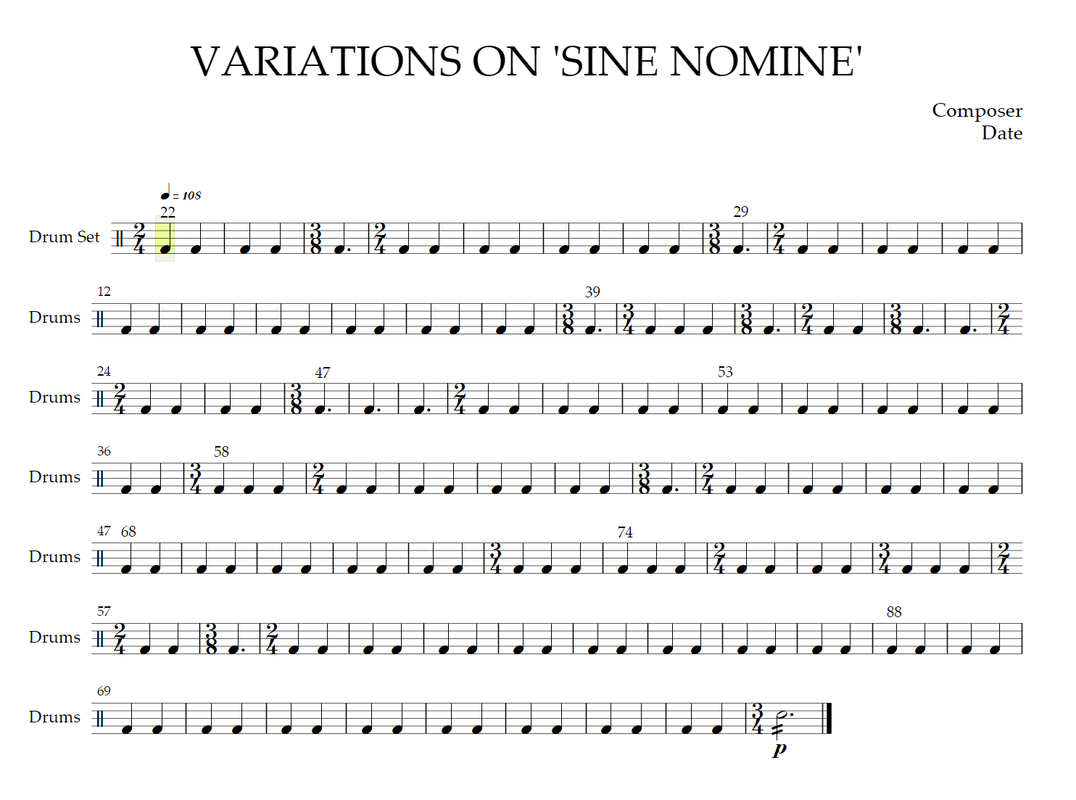

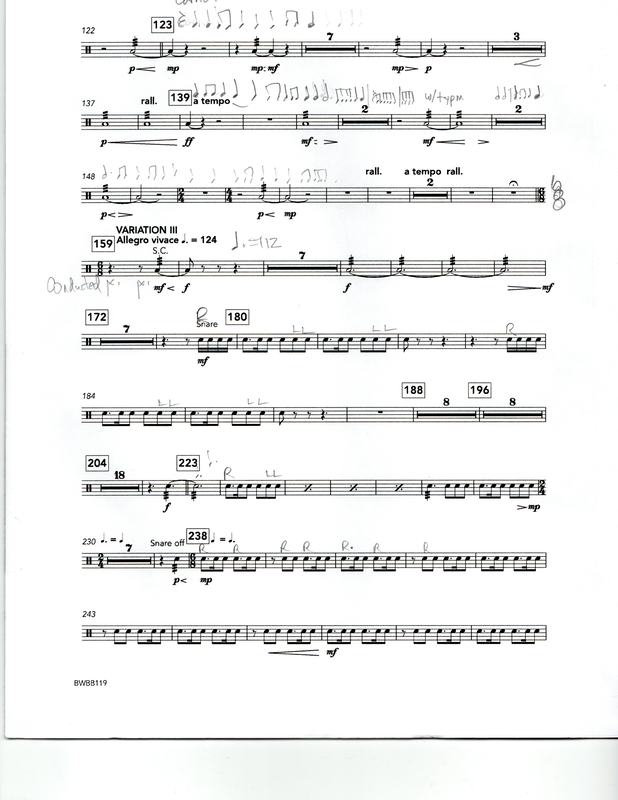

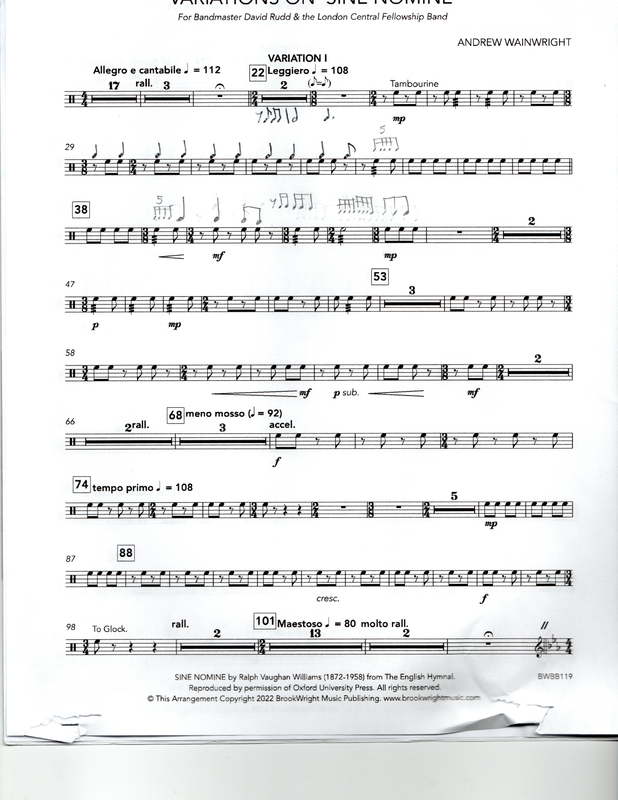

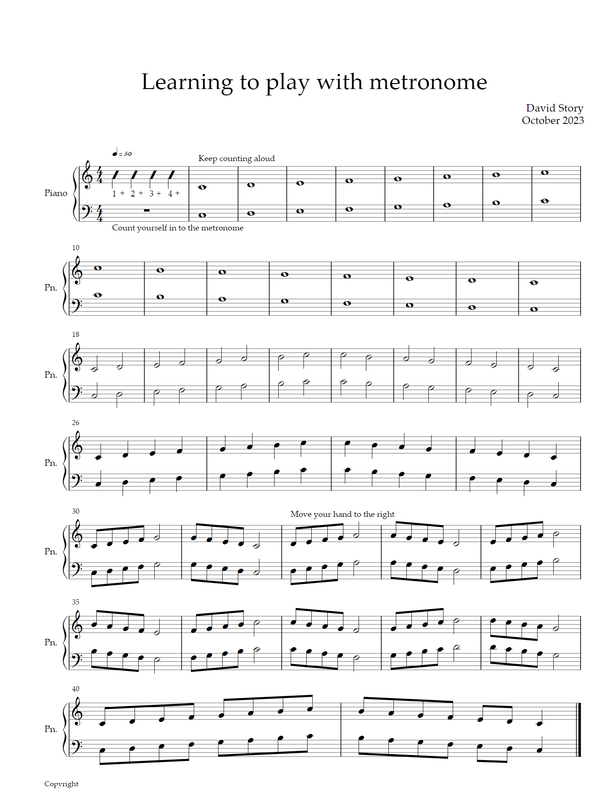

Learning to count rhythm is a primary skill in music reading. It will involve counting aloud, clapping hands, playing with a metronome and more. Below are examples of my preparations and practice strategies for a recent concert with the Metropolitan Silver Band in Toronto where I'm the drummer. As you can see, even trained musicians count and mark things up. David

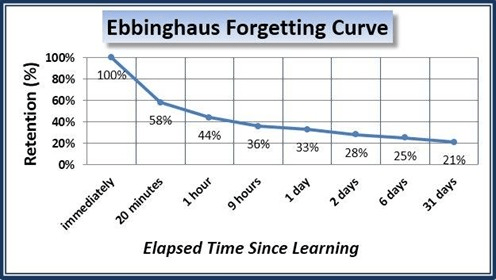

1. This chart helps to explain why taking notes is so important at a lesson. Don't just rely on the teacher's notes. Writing notes will help you to remember the class with more clarity.

2. This chart explains why the best time to practice is immediately after the lesson. 3. This chart explains why spaced repetition is so important. We forget most things we've learned if we don't heed the science of forgetting. 4. This chart demonstrates that we forget two-thirds of what we practiced the day before. 5. The chart should give you comfort that you are a normal learner. 6. The Harvard paper below offers some concrete helpful information on memorisation. If I can help you, call me. David References: Replication and Analysis of Ebbinghaus’ Forgetting Curve | PLOS ONE How Memory Works | Derek Bok Center, Harvard University I teach many retired professionals. Some are lapsed musicians; others are just starting out their piano journey. All of them are keen. To help out, I've taken notes of some of the characteristics of my successful students.

If I can help you with your dream of playing the piano, call me. David Tips for playing piano beautifully. Concert artists have dedicated years learning to play the piano beautifully. They have studied and mastered all the elements of their craft: repertoire, technique, aural skills, sightreading, performance practice, historical awareness, idiomatic knowledge, and more. However, they all had to start somewhere. So here is a starting point for beginners and intermediate pianists looking to elevate their interpretive skills.

This is a starting point for expressive playing. To develop a more sophisticated understanding one must transcribe the performance practice of professionals from different eras performing your pieces and compare the results. For example, when comparing performances of the first 8 measures of Scarlatti’s Sonata in E K380 over decades of recordings you will discover the diverse ways the musicians interpret the trills. Most start above the principle note, but not everyone. The intensity, tempi, and dynamics vary as well. If I can help you further, call me. David

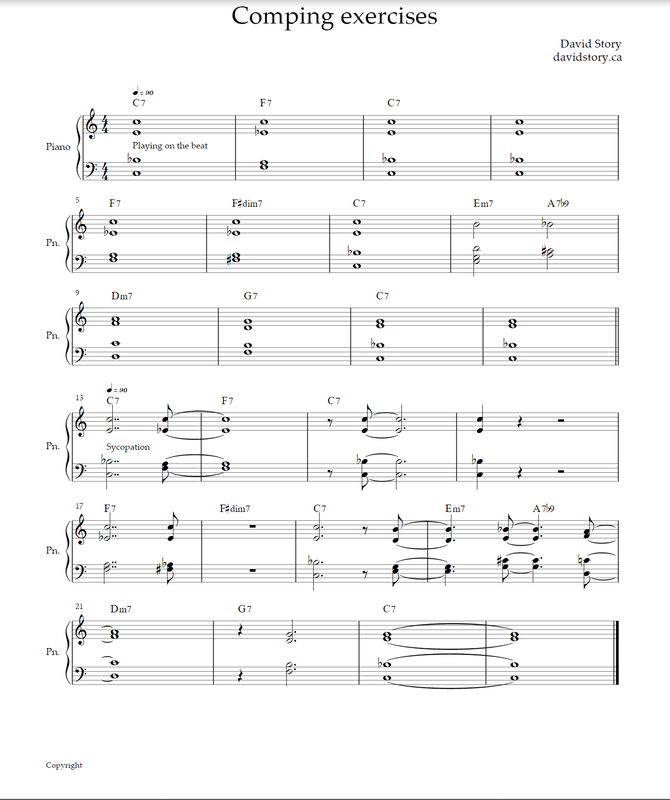

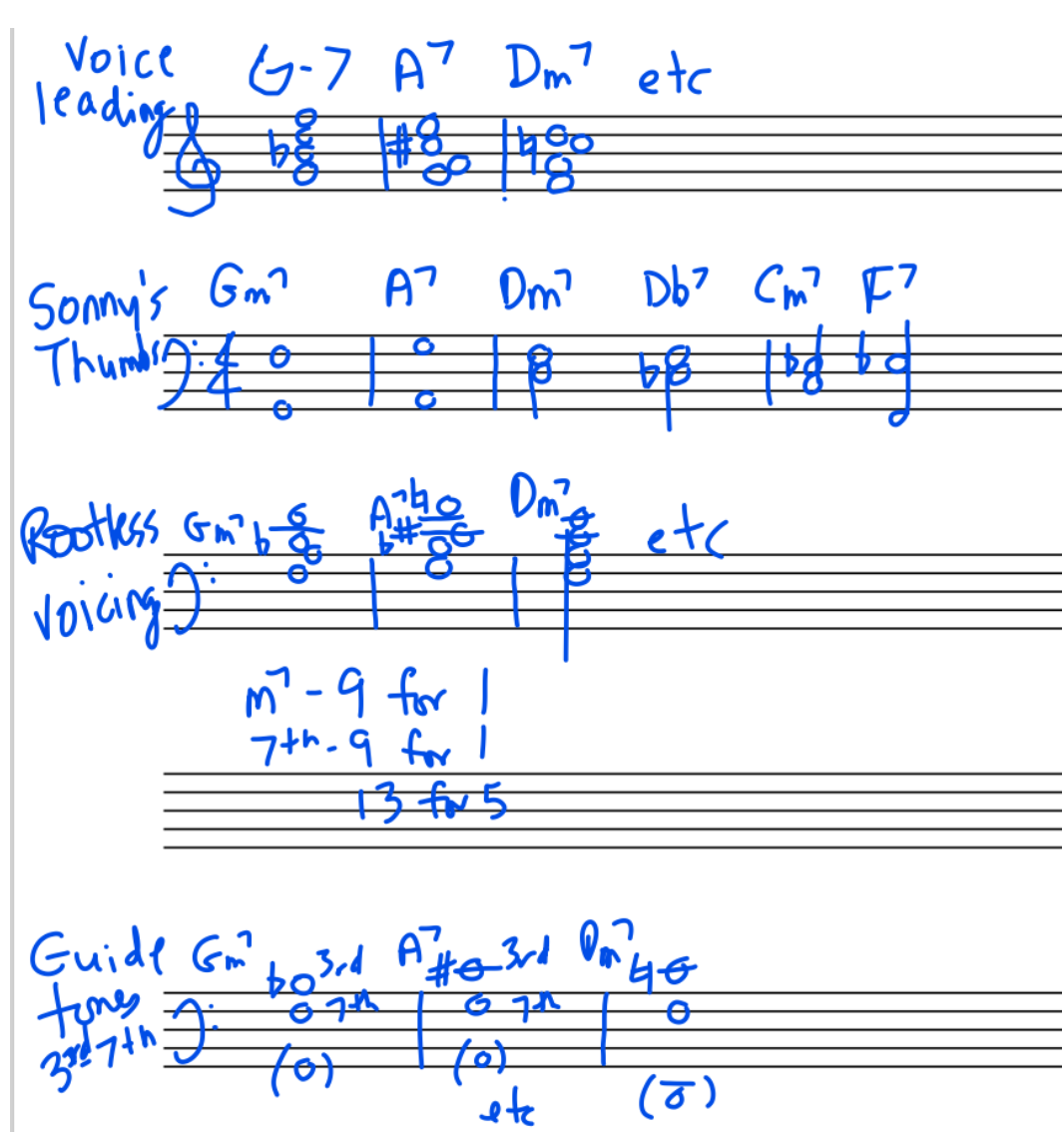

How to comp chords in swing jazz.

Keywords: Comping, comp, playing chords

How to use Play Along Tracks

Play along tracks are band recordings of jazz, blues, and pop songs minus the melody. You supply the melody when playing along. Here are some tips to get the most from the experience.

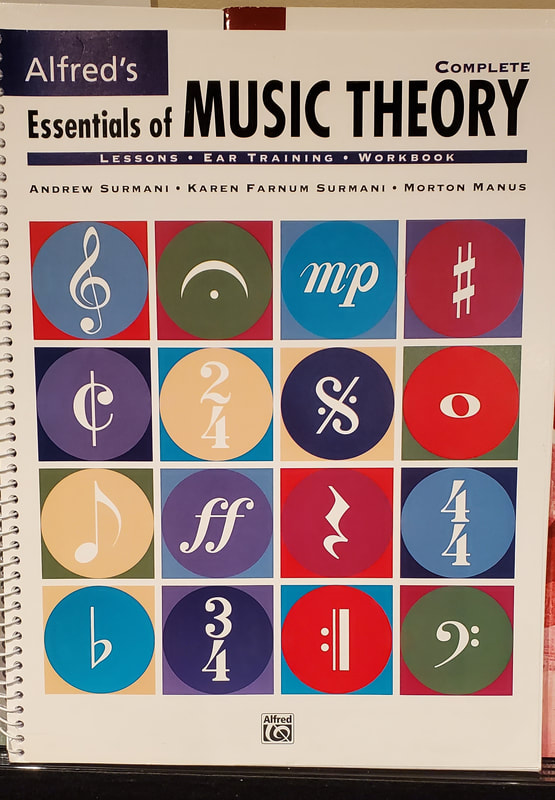

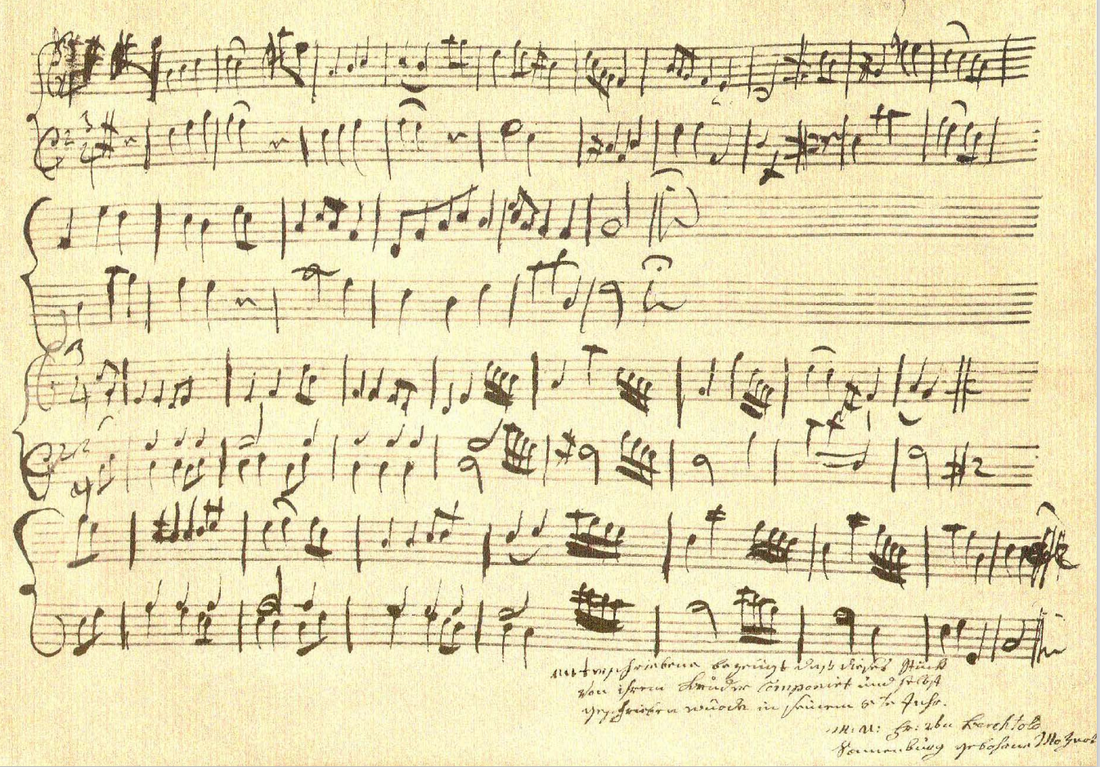

Apps for playing along. YouTube: (126) misty play along - YouTube iReal Pro: iReal Pro - Practice Made Perfect Band in the box: PG Music - Band-in-a-Box.com (bandinabox.com) If I can help you further, call me. David Sightreading is high speed pattern recognition. Pattern recognition comes from knowledge of rudiments and theory, piano technique, aural training, a deep knowledge of music history and stylistic performance practices and playing experience. A trained musician does not see a series of notes, they see patterns and relationships. For example, Mozart Minuet in G K 1e.

If I can help you, call me. David Tips.

1. Count aloud throughout. 2. Count one measure before you begin. 3. Practice counting and clapping first. 4. Record yourself clapping and listen back to evaluate your success or lack thereof. 5. Play one hand and count aloud. Record yourself playing and listen back to evaluate your success or lack thereof. 6. Play two hands and count aloud. Record yourself playing and listen back to evaluate your success or lack thereof. 7. Do this and similar exercises for the rest of your piano career. If I can help you, call me. David How to prepare to attend a classical music concert.

Revised 2024 Talking HeadsShort explanation This goes deeper Herbert von Karajan conducting the Berlin Philharmonic (1977) with scrolling score The score and parts are at the bottom of this page.

I recently returned from Scotland where I attended, Mostly Audio 2023, an audio/music/Ai workshop and conference. This video summarizes all that's wrong with Ai generated music while missing the creative possibilities of Ai.

My take aways from this video.

However, this video does raise interesting questions for music education. The structure, delivery methods, and content of musical education will need to quickly evolve to stay relevant. But I have a few questions. Relevant to whom? Do all students want to be creators or producers? What will be the nature of musical collaboration? Who will have time to listen to all this easily generated music? Who will care? Is the joy of making music in the work or the output? How will this be monetized? Did the "creators or producers" of this video have licenses to use the likenesses of John Coltrane? David I wish these apps had been available when I started playing piano as I was not a gifted ear player. In fact, I struggled. On top of this my teachers didn't stress aural development either because they were readers first. So, my development was glacial. Thankfully, things have changed.

How did I develop my aural skills? In college I was given proper ear training. Later, I took up the drums, learned countless tunes by ear, and wrote them down. For the last decade I've been teaching online where I don't always see students' hands clearly. My ear has learned to hear individual notes out of place. If I can help you, call me. David revised 2024 What an exciting time of learning. I was able to experience live coding, VR sound, Ai developments in musical education and more under the direction of young and exciting researchers. It was just what an old goat needed, some fresh ideas. One thing that did strike me was how dated the synthesizer music was. The young musicians were in the thrall of the 1990s. That took me by surprise. The walk from downtown to Napier University was lovely and peaceful.

I've been attending concerts for over half a century. That's a lot of concerts. Many have been completely forgotten, a few others can be recalled with some sort of prompt, and a small number remained seared in my mind. I counted seven concerts that changed me in some significant way. Here's the story of those concerts.

David Spend 15 minutes playing along with a recording.

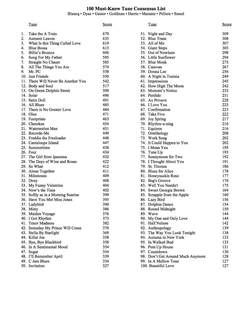

Have fun. David How to maintain your jazz repertoire. I recently attended a Q&A with Lynn Seaton, bassist, and Regents Professor from North Texas State University. My question to him was on how he maintains his repertoire when jazz gigs are no longer 6 nights a week. His answer.

What a great answer. After he practices, he rehearses from his list. How simple is that? My plan is to follow his lead for a year and see what happens. I'm going to use the list below as a goal for revitalizing my repertoire on the mallets. Happy practicing. David   "I have been a student with David for the past couple of years. While my primary instrument is Trumpet, I decided to take piano to broaden my knowledge. I have never had music theory, either in school or private lessons. David is taking me there through the piano. He assured me that all the skills I would learn through theory and practice on the piano were transferable to other instruments. David has a way of simplifying theory concepts, making them easier to understand. I had an opportunity to play Trumpet at a private service recently. Playing completely solo - no other musicians. One piece happened to be the one David and I were working on. Everything we had done came into “play” and those skills I have learned completely transferred to my Trumpet and I played the best I have ever played. When you ask yourself, “Do I really need to know this?” I can honestly say, Yes! and it pays off in performance quality." Barb Thank you, Barb. A New Student's Profile

The new student is a young professional with a keen interest in learning to play jazz piano. They took piano and trumpet lessons in high school. They have a basic understanding of music theory. Aural skills are excellent. Their program will include the following components:

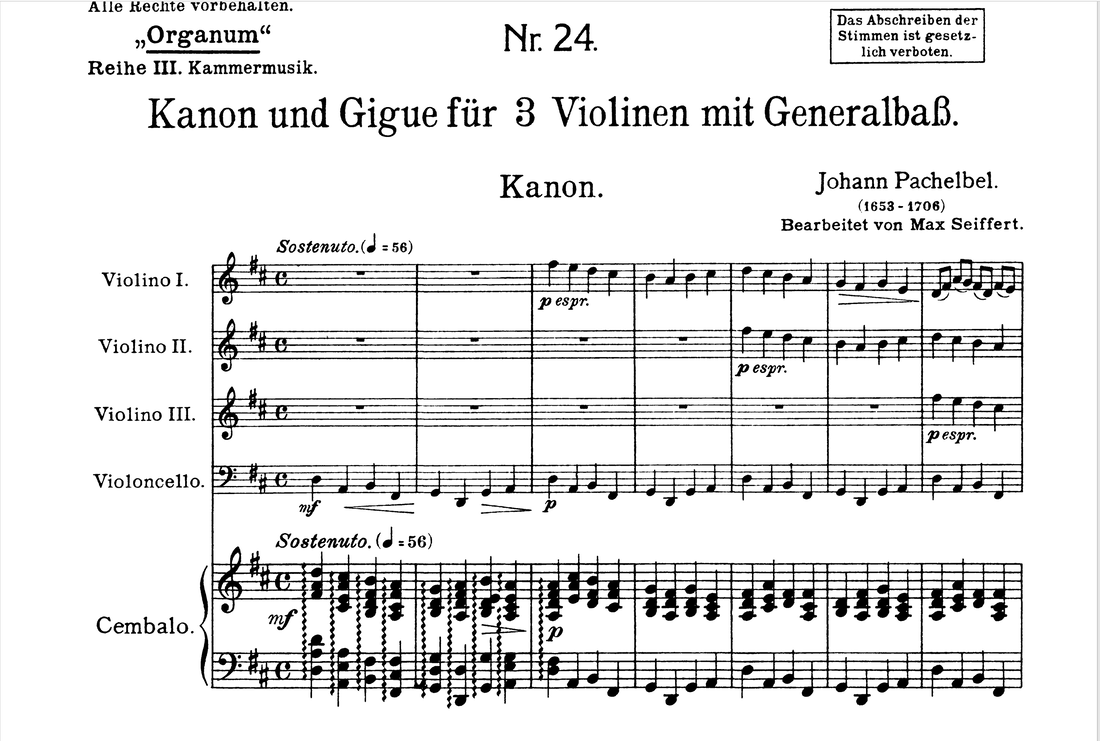

David This is a perennial favorite of music students. Let's look at a few key terms and concepts. Canon is a melody that accompanies itself at a staggered interval. Row, row, row your boat is a well-known example. In this canon the melody, played by the violinists, follows itself in two measure intervals. Ground Bass is the violoncello melody that repeats its 8 note pattern throughout the piece. Cembalo or continuo is the chordal accompaniment that is improvised behind the violins. In this video it is played by the organ and the lute. Notice that the cembalo left hand outlines the ground bass. Other notable orchestral canons can be found in J.S. Bach’s Musical Offering. The canons in that suite of pieces feature 2 violins chasing each other around accompanied by the continuo. Have Fun. David

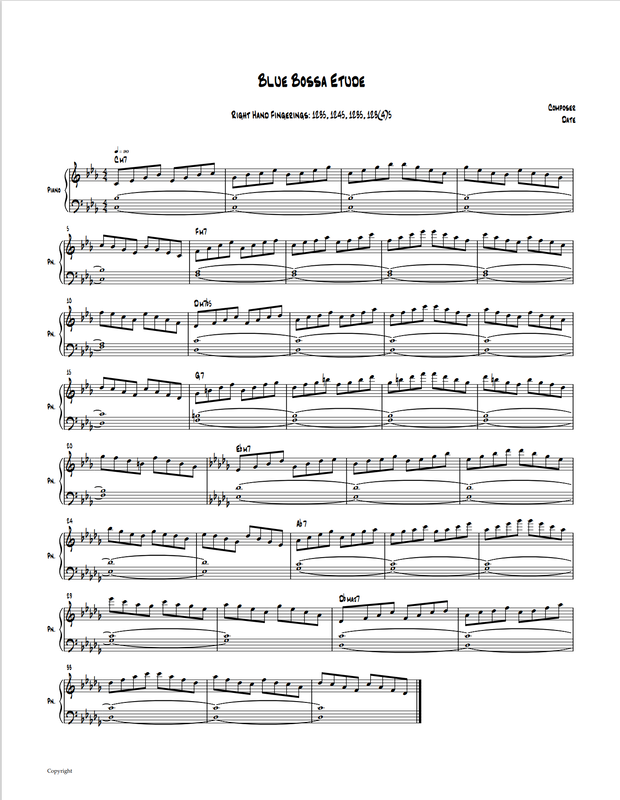

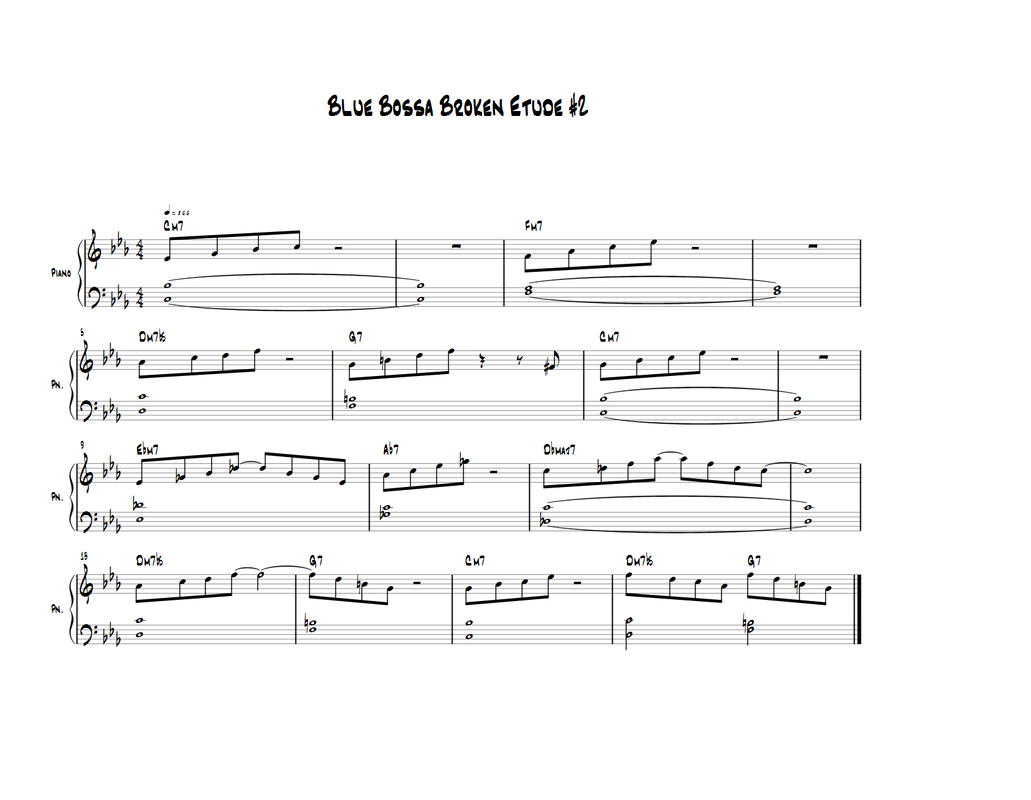

Have a great summer. If you would like to meet in the summer, call me. I have some limited availability. Cheers, david This is a lesson given to a student this week. Louis Armstrong, on the topic of how to improvise, said something to the effect, "memorize the melody, mess with the melody, and then mess with the mess." For beginners, this is the best advice I've ever come across. It is truly the shortest distance between A and B. Or jazz newbie to intermediate jazz student and beyond. Prerequisites: The student can already play. Therefore, it is a question of what to play and less of how to play it. Warmup: Two octave scales: C, F, Db, Bb, Eb Four note broken chords: C, F, Db, Bb, Eb Two octave arpeggios: C, F, Bb, Db, Eb Please use a metronome and practice different tempi, dynamics, and articulations. Etude Being able to play the broken chords is an important starting point in improvisation. Repertoire

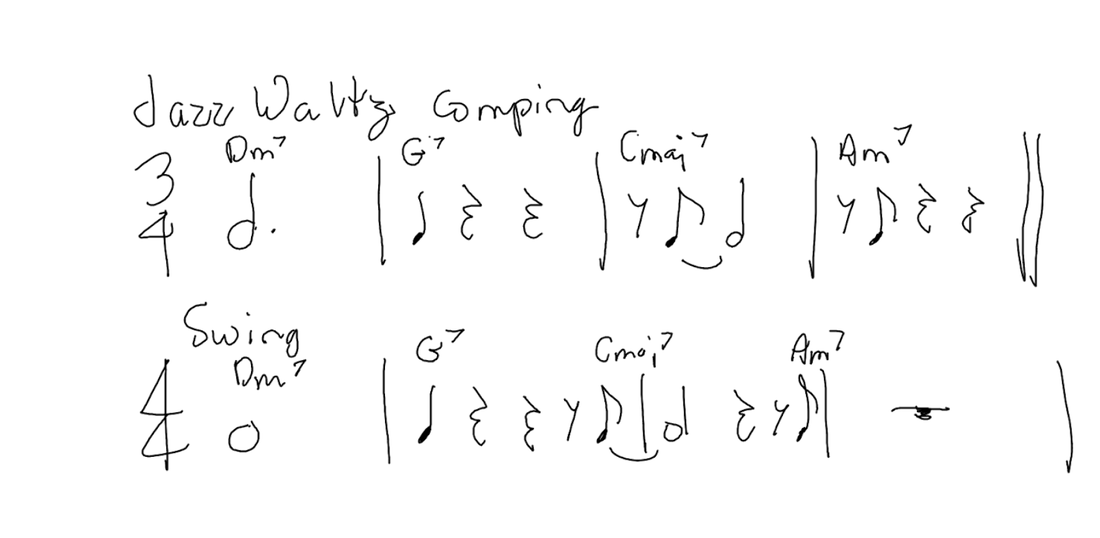

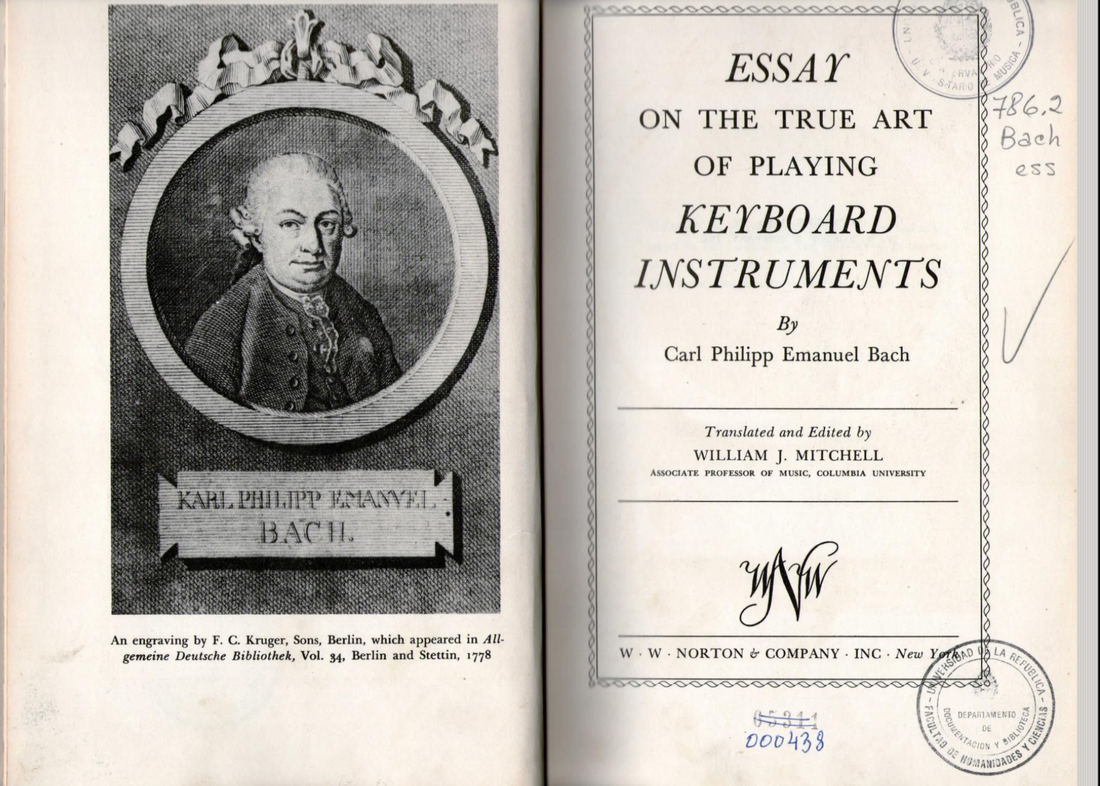

A selection of whiteboard Zoom notes from the past week or so. It gives a good snapshot of what goes on in students' classes. If you would like to join us, please contact me. David Years ago, while adjudicating piano exams in Aurora Ontario, I heard a young child came in to sit for her grade 2 piano exam. The performance was so beautiful, it took my breath away. Could you learn to play as well as her? Yes, with patient work. Thankfully to play the piano competently only requires you to follow a well-worn path. A path that has evolved over the last two hundred years beginning with CPE Bach's 1787 "Essay on the True Art of Playing Keyboard Instruments," to today's Adult Piano Adventures by Nancy and Randell Faber. I invite you to follow the links for more information. However, you will need to plan to succeed; so please consider the following conditions that you will need to meet:

If I can help you, please call me. David text: 905-330-1349 This guy explains how to sit on the piano bench correctly. He includes a discussion and demonstration of the correct distance to sit from the piano and the height of the bench. As he says, sitting correctly will help us play easier and avoid injury. Enjoy. David Consider each of the following before beginning.

Good luck. |

You've got to learn your instrument. Then, you practice, practice, practice. And then, when you finally get up there on the bandstand, forget all that and just wail. AuthorI'm a professional pianist and music educator in West Toronto Ontario. I'm also a devoted percussionist and drum teacher. Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed